IN WEBSITE ‘GALLERIES’, PLEASE CLICK TO VIEW ENLARGED IMAGES:

My maternal uncles were all creative, talented and much admired by my mother, Dorothy. The eldest, Stephen Sweet, was a naval architect and a talented watercolourist:

“When do we get learned the wolf whistle?” By John Sweet.

John Sweet, another of my maternal uncles, was a gifted writer and cartoonist. Unlike his four brothers, who all had careers connected with shipping, John’s was in the upper echelons of the Scout movement. He wrote amusing articles and drew cartoons for The Scout Magazine, and his ‘Scout Pioneering’ is still in print. Much admired by my mother (the second youngest in a family of eight) he and she both encouraged my and my two siblings’, creativity.

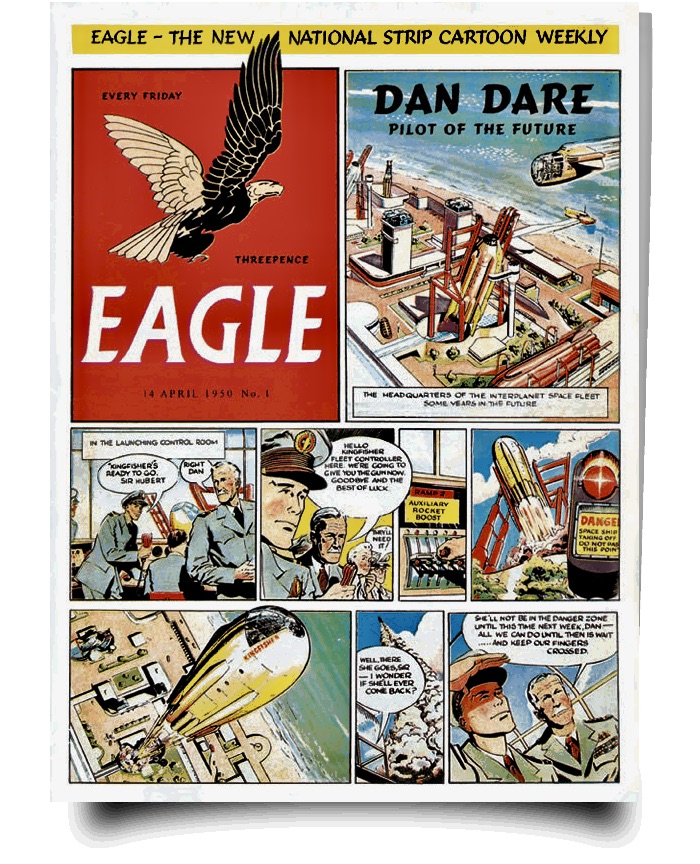

First issues of The Eagle, 1951 Dan Dare, created by Frank Hampson.

The work of both the above illustrators gave realism and mystique equal power. I found both illustrator’s work totally convincing. The historical reality or unreality of King Arthur’s knights, or the feasibility of life on Venus, were never an issue; the point is that the artwork gave access to another reality.

In secondary school, I found both science and arts subjects interesting, particularly zoology and botany. I set up aquariums and terrariums and spent a lot of time peering down a microscope. In the Sixth Form, I decided I wanted to go to art college, and combined my Advanced-level studies in zoology, botany and art with evening classes in life-drawing and pictorial composition at The Hornsey College of Art, becoming a full-time student in 1960.

Powerful Influences 1960 – 64

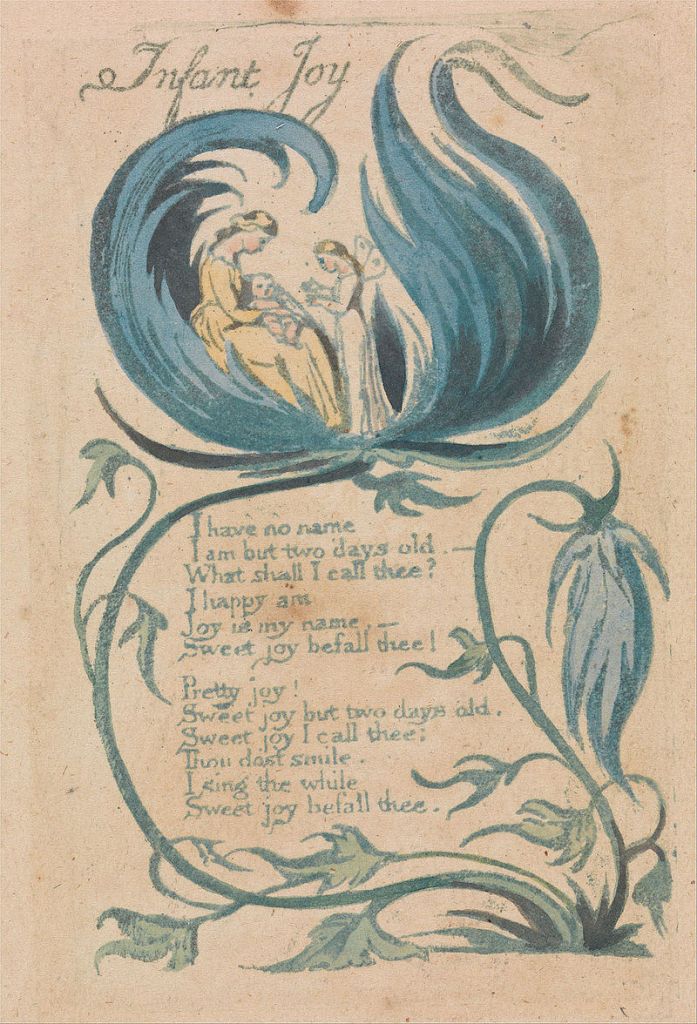

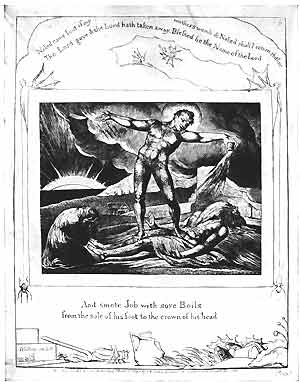

Apart from life-studio studies, and outdoor drawing, my early works at Hornsey art college were in a symbolist style inspired by William Blake, Richard Wagner, Carl Gustav Jung and, perhaps most of all, the spirit of the Greek philosopher Heraclitus. They all seemed to exemplify a notion that the human psyche has an innate access to the truth – an inner ‘greatness’ – the ‘Logos’ underlying the fiery life-energy driven by polar opposites. Eccentric as it may now seem, my aesthetic sense at the time was to dismiss anything that seemed to lack ‘polarity’. Besides Blake, Jung and Wagner, there were fellow painters at Hornsey who, to me, displayed that ‘polarity’, such as students Terence Howe and Dereck Pitstow.

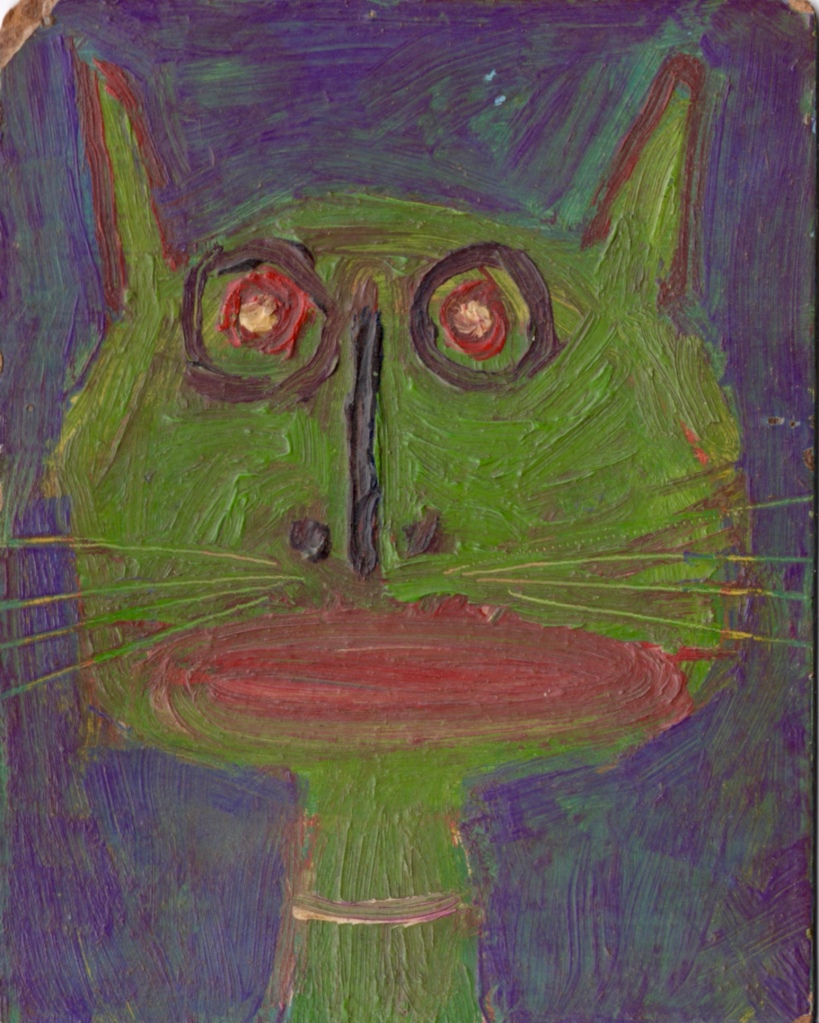

I was fascinated by a book in the Hornsey College library on ‘Psychotic Art’. The book included painters like Hieronymus Bosch, as well as works by asylum patients. I don’t recall if Richard Dadd was among them! Bosch wouldn’t now be considered insane, and I wonder if Louis Wain’s series of progressively more electrocuted cats had more to do with what he was being prescribed. But see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Wain Whatever – I found them all a great inspiration!

William Blake, one of my greatest heroes, was also considered mad by some of his contemporaries, and even by some of mine. Like Heraclitus, Blake wrote in engaging paradoxes and aphorisms: “A riddle or the cricket’s cry, is to doubt a fit reply.” “If the fool would persist in his folly he would become wise.” “Eternity is in love with the products of time”

The prevalence of flames in Blake’s designs, and his idea of ‘contraries’, links him to Heraclitus, and adumbrates Jung’s view of libido, or psychic energy, as undergoing many transformations, and, like electricity, having positive and negative polar directions, outwards towards the daylight world, and inwards to that of the psyche.

The 19 year old Samuel Palmer met William Blake in 1824. Possibly the best, written description of his own compositions is Palmer’s response to William Blake’s woodcuts of scenes from Virgil: “They are visions of little dells, and nooks, and corners of Paradise; models of the exquisitest pitch of intense poetry. I thought of their light and shade, and looking upon them I found no words to describe it. Intense depth, solemnity, and vivid brilliancy only coldly and partially describe them. There is in all such a mystic and dreamy glimmer as penetrates and kindles the inmost soul, and gives complete and unreserved delight, unlike the gaudy daylight of this world. They are, like all that wonderful artist’s work the drawing aside of the fleshly curtain, and a glimpse of that rest which remaineth to the people of God.” (Life and Letters of Samuel Palmer A.H. Palmer 1892)

Samuel Palmer – Self Portrait 1826

Ashmolean Museum Cambridge

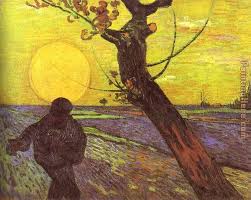

Terence Howe and myself were very taken with Geoffrey Grigson’s ‘Samuel Palmer, The Visionary Years’ (1947) which argued that Palmer should be seen as a great painter in his own right, not merely as a follower of Blake. But Palmer was, like Blake, a very linear artist, and this not only makes him seem very modernist at times – he has sometimes been compared to Van Gogh – but also rather medieval.

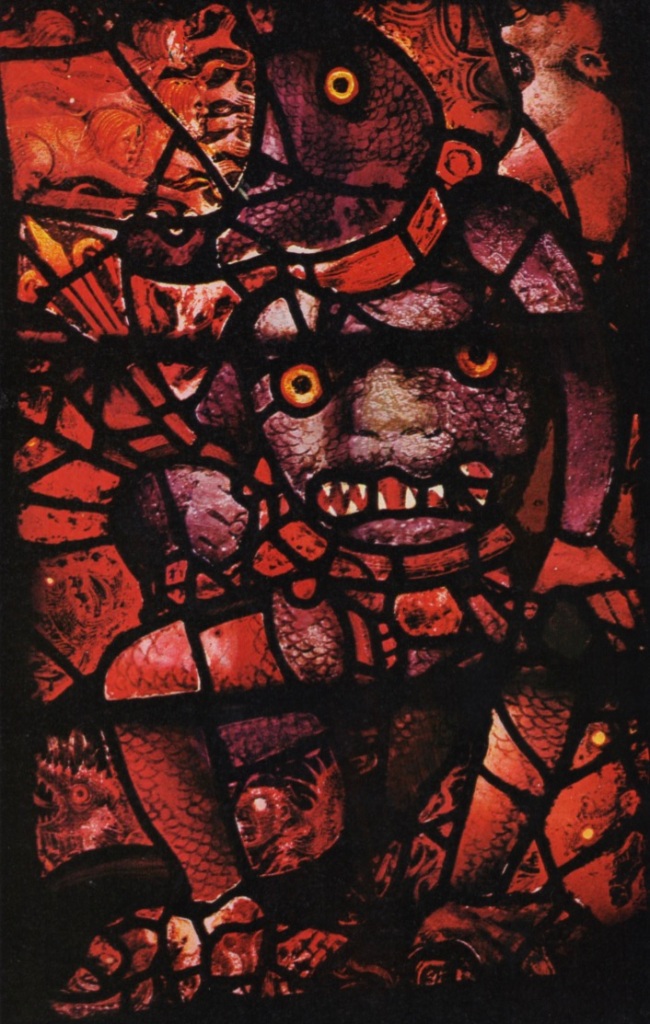

Another very influential book among some of my fellow students at Hornsey was ‘English Stained Glass’ with an introduction by Herbert Read, magnificent photography by Alfred Lammer, and text by John Baker (Thames and Hudson 1960)

In 1962 my ‘6’x4′ canvas The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden’ was accepted for inclusion in the Young Contemporaries exhibition in the the RBA Galleries in Suffolk Street, SW1. The work exemplified my (above-mentioned) perception in terms of ‘polarity’ – in particular that of subject and object.

At the YC Forum, of which I had not been aware, my ‘Expulsion’ painting was reportedly singled out by Anthony Caro for its imaginative power. In fact, perhaps influenced by Blake, I always felt a desire to write something on my picture surface, but could never think what – at best it would be ‘Oh’. After all, the picture is about an awakening of consciousness after eating of the Tree of Knowledge – rather as the Royal College of Art students were doing.

In the Young contemporaries show it was the ‘Pop Art’ paintings of a rising generation of Royal College of Art students that attracted the most attention. Influenced by their slightly older and more experienced fellow-student R. B. Kitaj, they questioned the exclusive influence of abstraction, in their own paintings deploying recognisable imagery from history or contemporary culture. When, at the Y. C. forum, Carel Weight objected to David Hockney’s inclusion of script on his large canvas ‘A Grand Procession of Dignitaries in the semi-Egyptian Style’; Hockney pointed out that Egyptian painting was frequently covered in writing from top to bottom.

Hockney is two years older than me, and I have been aware of his glittering, extravert career running parallel to my own low-key obscurity, but I don’t underestimate his genius, or his importance in reasserting painting as an art deploying draughtsmanship and imagery.

At Hornsey Art College ours was the last year group studying for the N.D.D. (National Diploma in Design) which was about to be replaced with the Dip. A.D. (Diploma in Art and Design). Art college entry requirements would become stricter in terms of school certificate qualification, although no more so in terms of artistic talent. Caught between avant-guard and traditional priorities, and with a more mixed and less upper-class range of students than in some art colleges, Hornsey tutors seemed worried lest Hornsey fail to meet the new standards.

In many ways there was confusion. While drawing from observation – out of doors and in the life studio – was still of central importance, our painting professor, Maurice de Sausmarez, also introduced a ‘Basic Design’ course, which explored the purely abstract dynamics of colour and visual form. This, it seemed, addressed the increasingly perplexing issue of what exactly an art college was supposed to teach. The answer seemed to be a new ‘academicism’ which would underpin all visual art, craft and design, and emulate the modernist teachings of the Bauhaus.

But in the early 1960s abstraction was already being challenged by the emerging ‘Pop’ artists as well as by the figurative paintings of Bacon and Freud. ‘Conceptual Art’ and ‘Performance Art’ were perhaps already implicit, along with the notion that creativity need not place emphasis on a physical commodity.

Perhaps with this in mind, in 1969 Peter Kardin of St. Martin’s College of Art introduced a curriculum in which new students were locked into a white studio for eight hours a day for the rest of the term…“They were given no explanation, just a few materials…..a bag of plaster, a roll of paper, a block of polystyrene and given no instruction, no advice and no response” – except that they were not allowed to leave or to speak. Some apparently found this liberating, others oppressively authoritarian. (See HORNSEY 1968 the art school revolution, by Lisa Tickner 2008)

Having left college in 1964, by 1968 I was already employed as a qualified art teacher, seemingly remote from art student ‘Sit-Ins’. Yet many of the issues that arose were just as relevant to the place of the arts in primary and secondary school curricula. While governments wanted to know what art education actually delivered for the taxpayer, Hornsey students, and some staff members, felt genuine dissatisfaction and unease with any such definitions. They were also concerned about new art school entry requirements, and, furthermore, by questions of status contingent on plans to merge university and technical colleges into polytechnics. In fact the Hornsey Art College was eventually subsumed to a ‘Middlesex University’.

Despite genuine indignation and eloquent speechifying from both student representatives and visiting celebrities in 1968, the protests seem to have been characterised by quite appropriate introversion and vagueness. Attempts at defining, rationalising or justifying art education often miss the point that it is the art that teaches – Its contribution cannot be predicted or defined, except in the uncertain terms of an evolving culture and society. Tangible benefits, such as improving children’s language skills or helping the economy, may or may not result as extrinsic spin-offs of an unpredictable enlargement of consciousness.

Heraclitus of Ephesus knew this very well in the 6th C BCE – “Man is most nearly himself when he achieves the seriousness of a child at play.” Art raises unexpected questions even when toeing the line – as the critic Waldemar Januszczak once pointed out, no one had told a Renaissance artist painting The Crucifixion whether or not Christ had cut his toenails.

British Modernists and Neo-romantics

As well as abstraction and Picasso, it was the visionary work of Blake and Palmer which influenced the work of many British painters in the early 20th C, including such ‘Neo-romantics’ as Graham Sutherland, Paul and John Nash, and visionaries like Stanley Spencer. Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud too were aware of Blake’s importance. Like other British modernists with romantic leanings, they were also in awe of Albrecht Dürer’s great contemporary, Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, 1506-1515

At Hornsey, I wrote my N.D.D. dissertation on Matthias Grünewald, arguing that there were similarities with British ‘Visionaries’, such as a sort of rubbery expressive distortion, linearity, what might be called ‘ripples and silky flows’, and a luminosity seeming to come from within. I implied that these were evidence of similar psychological disposition rather than of artistic influence.

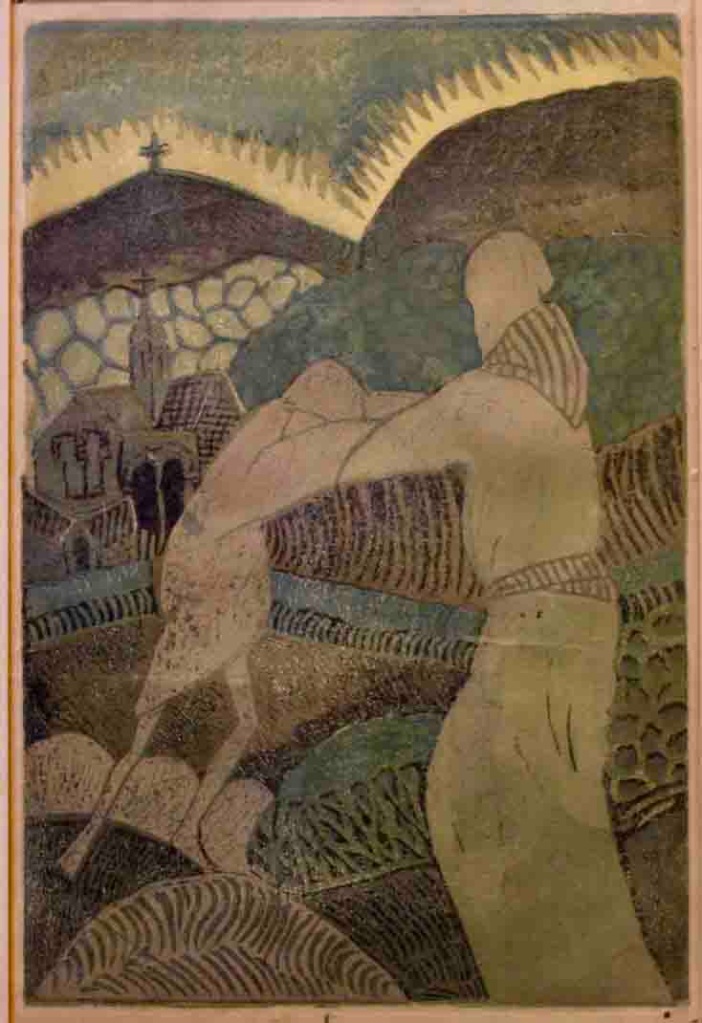

Nevertheless, I and some fellow students were indeed influenced by encounters with such visionary styles and subject matter. (As John Wormell, one of our tutors, said to me at the time “Trust you to write about Grünewald!”) A medievalist intensity can be glimpsed in my ‘Prodigal Son’ linocut and other of my works from 1960. The fact that I later became less overtly expressionist is in itself significant. In Britain, the emotive, moral and intuitional issues of Christianity, or at least of the human condition, lingered in post-war modernism, even affecting the works of atheists like Bacon and Freud, but perhaps went no further. We shall see.

Indirect Influences

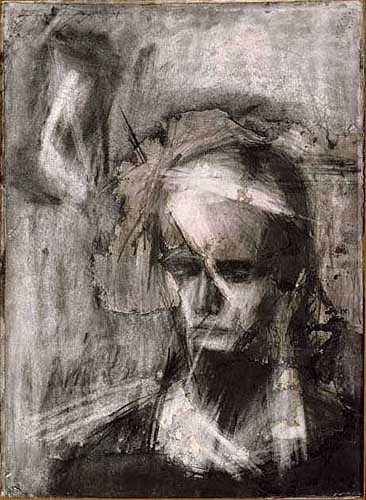

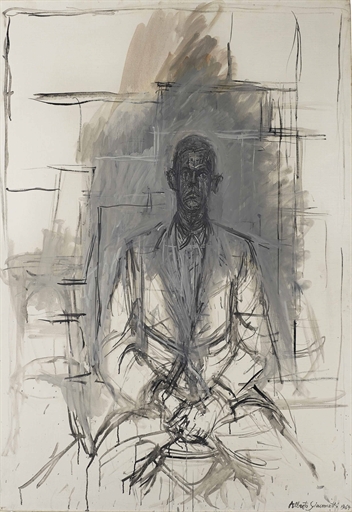

Influences from other contemporary artists came directly or indirectly via teachers and fellow students. I knew nothing of Frank Auerbach or Giacometti at the time, but their influences somehow filtered into my drawing. One possible source was Julia Wolstenholme, whom I met comparatively briefly. At the other extreme were tutors like Jesse Cast, John Titchell and Frederick Cuming, who encouraged a more reticent objectivity.

National Portrait Gallery, London

Cast had in fact been a pupil of Henry Tonks at the Slade School of Art, and Titchell, Cuming, even Bridget Riley, had all been influenced by a tradition of observational drawing, derived ultimately from the Renaissance, at the Royal College of Art.

At art college in the 1960s, it would have been impossible to ignore the American abstract expressionists, and artists like John Hoyland, who now and again tutored at Hornsey, made sure we didn’t. Finding myself bereft of my formerly insistent ‘visionary’ instinct, I identified with the performative element in Jackson Pollock’s work – (‘in the moment’) and found the vibrant presence of his large canvases on the gallery wall enviable and compelling. This influenced some of the paintings I later did in Newcastle, though they were always on-the-spot responses to a subject or setting.

Graduating from Hornsey in 1963 I commenced an Art Teacher’s Certificate course in Newcastle Upon Tyne. The Big names at the Art College were Victor Pasmore and Richard Hamilton, who had also established a ‘Basic Course’, which I attended under the inspiring tutelage of the artist Rita Donagh. We also attended two lectures by Hamilton; one was on Marcel Duchamp’s ‘Large Glass’ – otherwise known as The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even – which he had reconstructed; the other was about Pop Art. Ironically, Hamilton disparaged Hockney, while affirming that he himself was ‘The Father of Pop Art’, which was, of course, as much about significant imagery as abstract form. Arguably, the art of painting has always been deeply concerned with both.

The post-graduate year in Newcastle in 1963-4 was my first experience of living away from home. I found the new surroundings exciting and collaborated with a fellow student, the sculptor/painter John Richter, on art projects both in the city and the Northumbrian countryside.

As well as artworks inspired by ancient Egypt, Richter was making small sculptures of walking men, inspired both by Giacometti and by Samuel Becket, particularly the latter’s extended soliloquy, “From an abandoned work”, written for radio in 1957. John found that he could relate to Becket’s metaphor of vagrancy.

“…I simply will not go out of my way, though I have never in my life been on my way anywhere, but simply on my way.” (Samuel Becket, From an Abandoned Work, 1958)

I was already impressed by the visionary expressionism of Oska Kokoshka. In addition, John Richter drew my attention to the defiant independence of David Bomberg’s work.

Exponents of ‘Land Art’ such as Richard Long or Andy Goldsworthy had not even left Art College at the time that, mostly at John’s initiative, he and I were making sculptures from marine debris beside the Tyne (see below) or using natural materials to make art in remote places (left).

To us, merely making a motorcycle trip to the Cheviot Hills could seem enough of an artwork in itself and more than justified a day’s neglect of theoretical study!

INDEPENDENCE

After Newcastle, John Richter found work in Scotland as a Water-Bailiff. He subsequently travelled to Egypt, camping alone in the desert in the presence of its vast monuments. Meanwhile, I returned to London where Terence Howe introduced me to a Cabala group – The Society of the Hidden Life – which met in Highgate. Despite its esoteric basis, and its affiliation with Jungian ideas, the teacher, Anthony Potter, regarded me with some disapproval. A number of the group’s members were former Hornsey art students, but Potter, whose day job was editing an advanced technological magazine, ‘Automation’, seemed sceptical about the value of art and artists. However, one important aspect of what was called ‘The Work’ was emphatically practical: one must leave Mother’s apron strings and become materially independent. By the time I left the group, in about 1974, I had made considerable progress in that regard – as well as in esoteric studies. I have written elsewhere* about Anthony Potter and another esoteric teacher, Barry Long, whom I met in 1980.

* https://johnnpearceartist.com/art-and-reality/

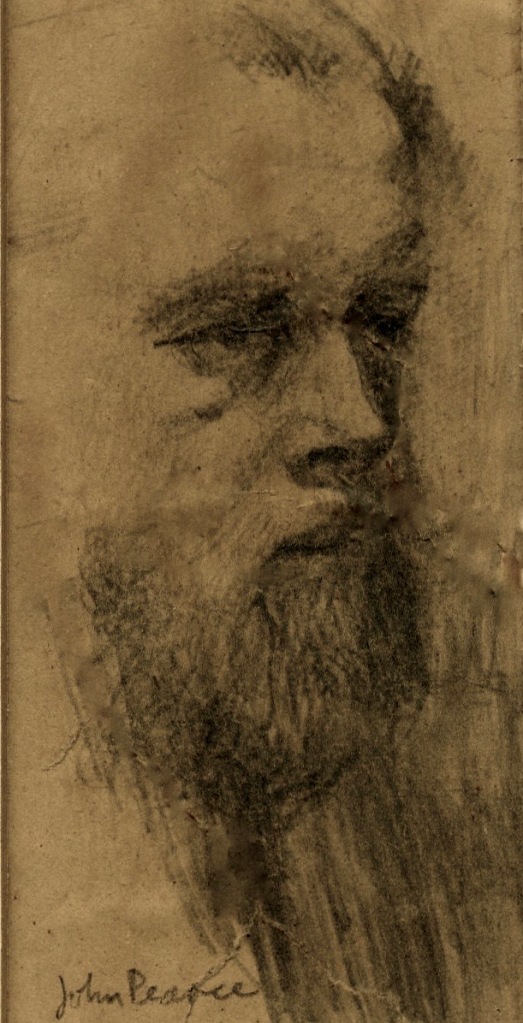

Anthony Potter, Christian Cabalist