“Men’s curiosity searches past and future

And clings to that dimension. But to apprehend

The point of intersection of the timeless

With time, is an occupation for the saint—“

— from “The Dry Salvages” – in Four Quartets, T.S.Eliot

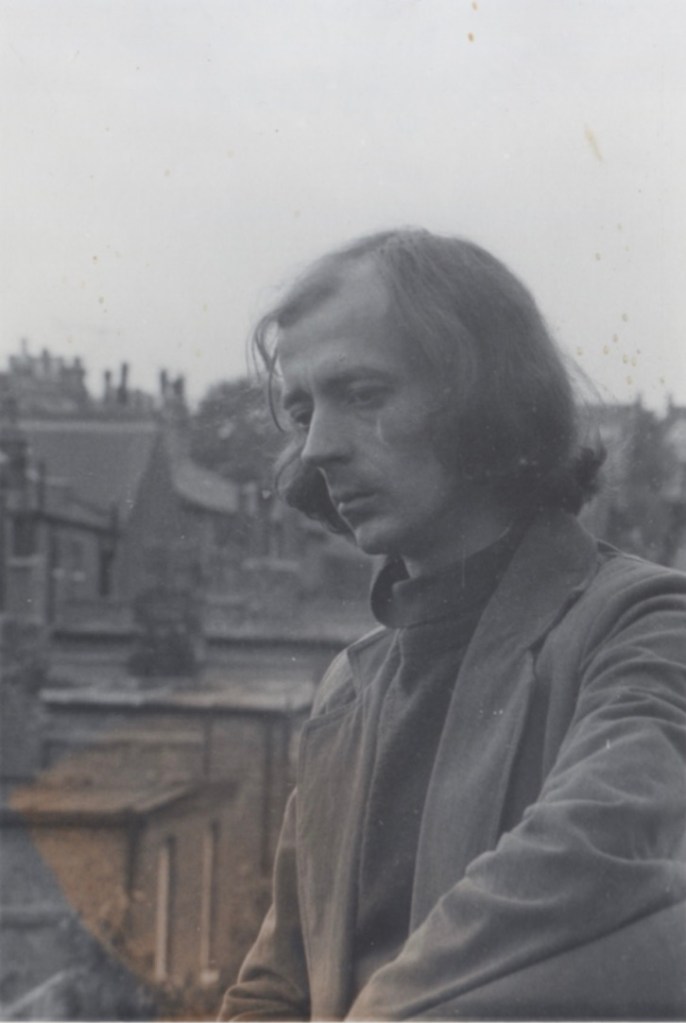

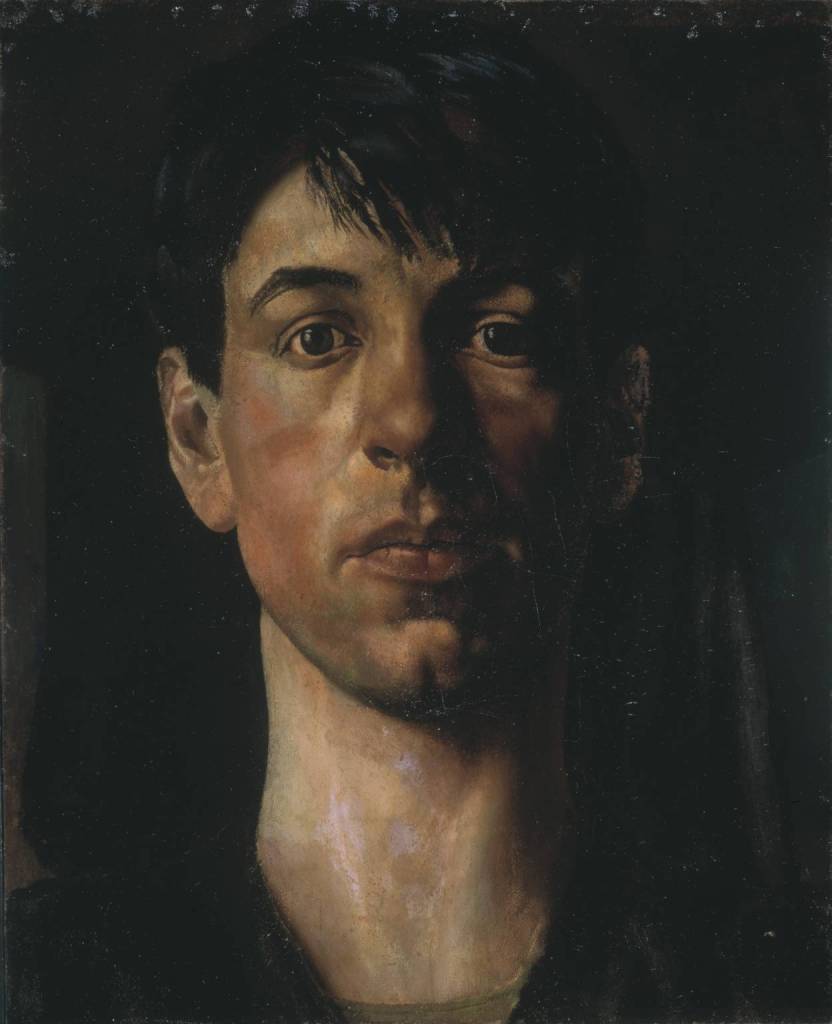

By the mid 1970s, I knew that I wanted to draw and paint, but without any prevision as to what, how or why. Not singing from any hymn book, ancient or modern, I began working directly from the subject. At about the same time I noticed Lucian Freud’s views from his studio windows, which showed a similar absence of stylistic preconception, and a seeming independence from the history of art or the art world in general.

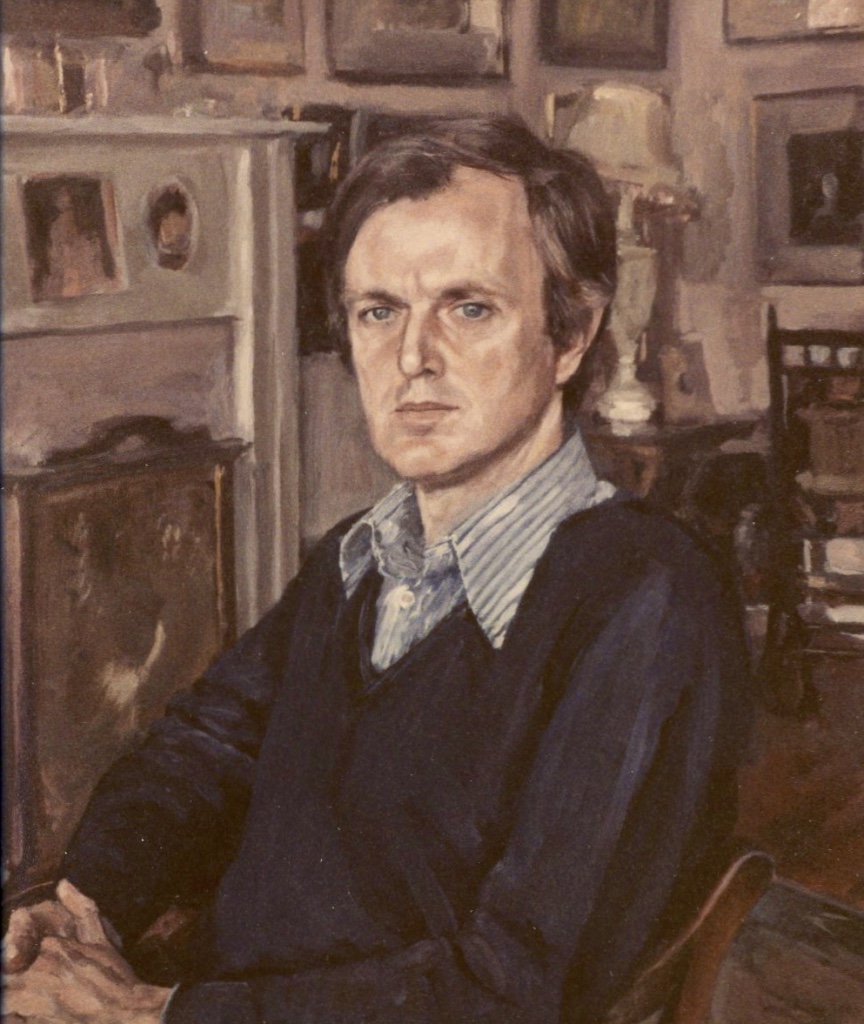

Myself in 1972 >

In Freud’s pictures the urban back gardens are hardly visions of an Earthly Paradise. Unlike Stanley Spenser and Samuel Palmer, Freud offers a secular view of life and nature, inseparable from change and mortality.

PLEASE CLICK TO VIEW COMPLETE IMAGES:

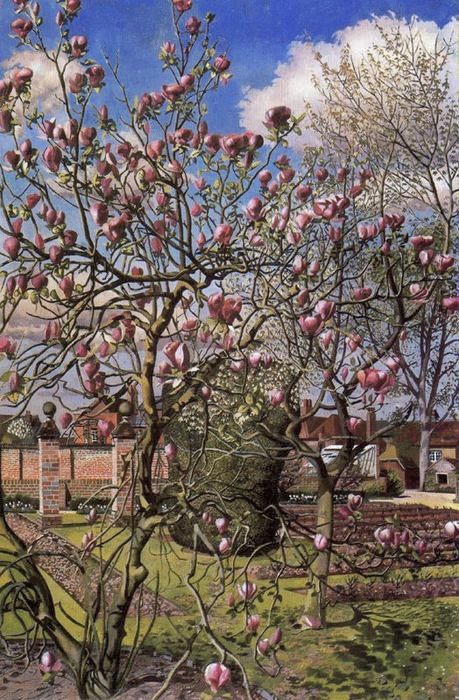

Stanley Spencer was more than a painter of sepulchres and shrouds. His second wife, Patricia Preece, not only encouraged Stanley to paint numerous landscapes and gardens in and around Cookham, to help pay the bills, she also posed for some extraordinary ‘in your face’ nude portraits. It’s hard to believe Lucian Freud hadn’t seen any of these, but Freud, who seldom gave interviews, nevertheless flatly denied any similarity, citing Spencer’s sentimentality and inability to observe (Geordie Greig, 2013 ‘Breakfast With Lucian’). But Spencer evidently did work from observation, and often ‘on site’ around Cookham. Like any other painter, he transmuted raw sensory data in his own way. Some would see even his observational landscape paintings as original and visionary. His early self-portrait is reminiscent of Samuel Palmer’s.

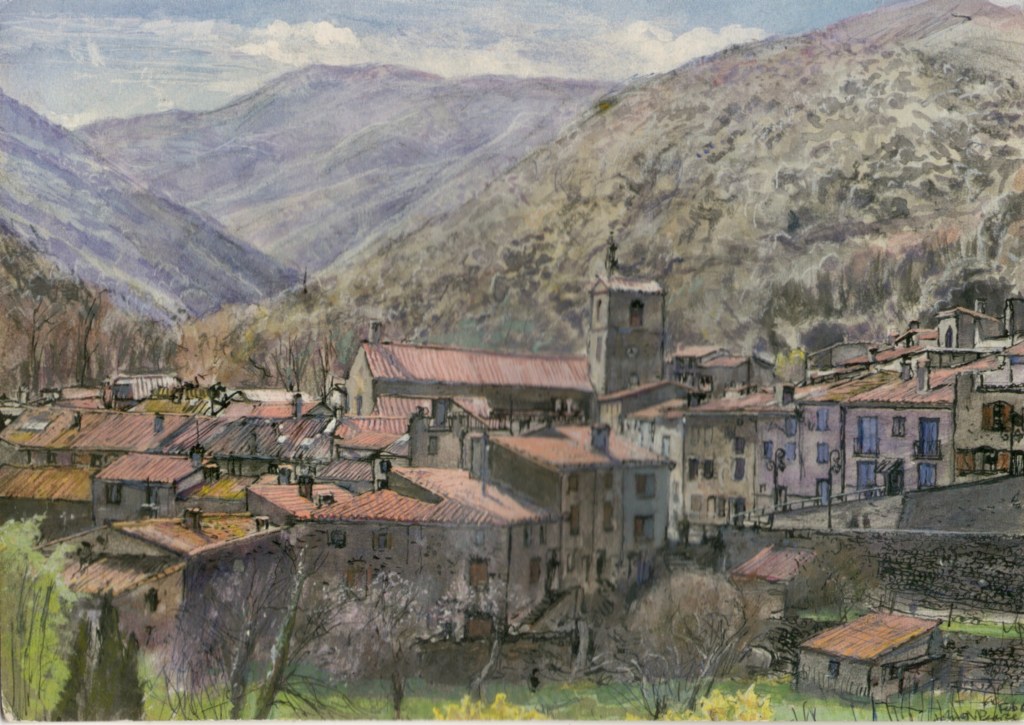

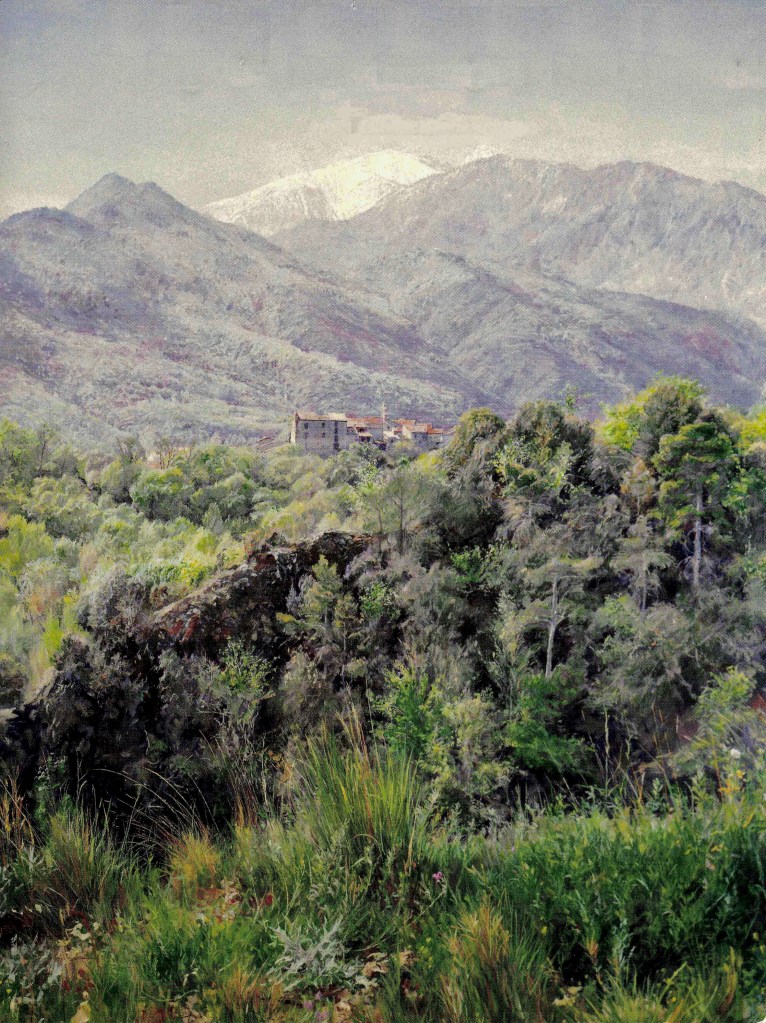

In 1974 & 1975 I made a series of quite large paintings in rural settings, perhaps because the forms of nature already looked a bit abstract.

I became fascinated by the interplay of light with grass and foliage. I completed these works in no more than a few days, until, In 1980, working on a painting specifically to enter for the G.L.C. ‘Spirit of London’ prize, I found myself working intensely on location seven or eight hours daily over four weeks, and striving to keep pace with plant growth and changes of light as the summer advanced.

Please click on the images to view the galleries

A painting that suggests some synchronicity between my approach and Lucian Freud’s at this time is his extraordinary ‘Two Plants’, purchased by the Tate in 1980. Begun in 1977, the painting took three years. It seems to me that Freud must have begun this work towards the upper central region of the canvas, where the tiny leaves of the creeper are still green, but during the time he gradually worked away from that initial point, the leaves began to fade to a desiccated pallor. The time spent on the painting has thus become part of its subject. Freud said of this picture “I wanted to have a really biological feeling of things growing and fading and leaves coming up and others dying.” https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/freud-two-plants-t03105

Freud evidently had a lifelong fascination with plants, which often feature in his work. His so-called ‘naked portraits’ attract more comment, and may reflect a similar biological fascination as part of his interest in people. They too are works of extended scrutiny in which the artist’s demands on the sitter must have been considerable, but Freud could interact with and influence them in ways he could not with growing vegetation.

Portraiture has always been an informal aspect of my painting, but in 1982 I wanted to enter for the newly instituted John Player Portrait award. At the time entrants had to be 40 or under, so it was my last chance. Having recently met the Australian spiritual Guru Barry Long, a man with a warm but formidable persona whose teaching was about inner stillness, I reckoned he’d be a good sitter. I spent many weeks on the work, which was indeed shortlisted for the prize and exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery in 1983. Some commentators thought I was influenced by Freud, but any similarity of approach has arisen independently.

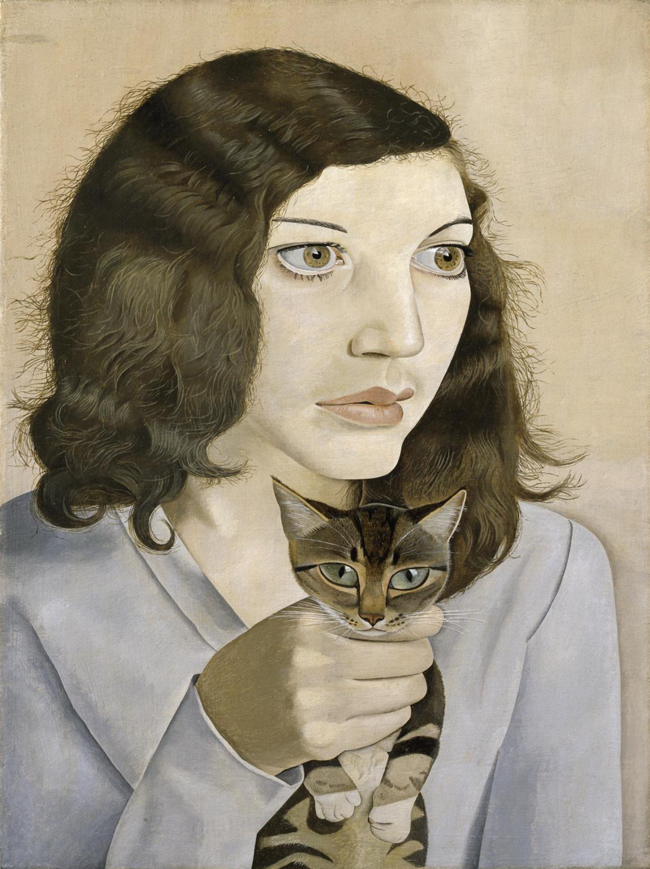

Works such as Freud’s ‘Girl with a Kitten’ 1947 are, in my opinion, incomparable.

Besides ‘Blackberries in August, Muswell Hill’ the 1980 ‘Spirit of London’ exhibition included another work, ‘Gardens, Whitehall Park’, which I had painted in 1979, and which was the first of many I was to paint in the semi-wild garden of my friend Clement Griffith. Originally I meant to include Clement in the picture but, after he had posed in the garden for rather long periods, I realised that the artificial stillness imposed on him was at variance with the timescale of natural change that I felt in the garden. So I painted over the figure, but, because the painting is acrylic, Clement is still there, hidden under the grass and roses.

It was subsequently bought from me by a dealer and collector, Michael Dickens (1942 – 2020), who considered the painting was in a contemporary manner not unrelated to Stanley Spencer’s. He was also intrigued by the story of the hidden presence of Clement.

Despite some contrarian opinions, Michael had considerable discernment as well as charm. He had been brought up in Bourne End near Cookham, the home of Stanley Spencer, and became a friend of the painter Nancy Carline as well as an authority, not only on Stanley Spencer, but also on Stanley’s first wife, the painter Hilda Carline, his second wife Patricia Preece, and Preece’s close friend, the artist Dorothy Hepworth.

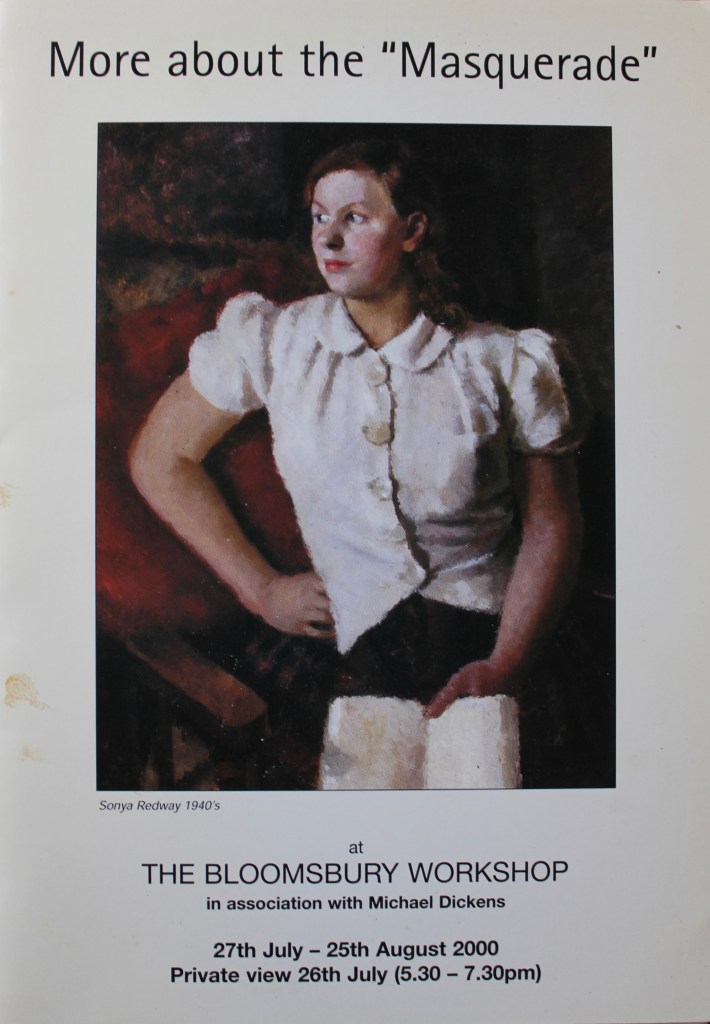

Michael later promoted and curated innovative exhibitions of Dorothy Hepworth’s paintings at the Bloomsbury Workshop, The Court Gallery and The National Theatre in London, revealing ‘A remarkable deception … in her lifetime, Dorothy Hepworth had allowed her paintings and drawings to be sold as the work of her lifelong partner Patricia Preece who “masqueraded” as the artist. The two women deceived the Bloomsbury artists but also other notables in the art world such as Augustus John’ (exhibition note by Michael Dickens, Bloomsbury Workshop, 2000).

Michael was a music lover and a great ballet fan. In his youth he’d assisted backstage at the Royal Ballet, becoming friends with Fonteyn and Nureyev, but his main career was in medical research as an electron microscopist, eventually working at King’s College, London with Maurice Wilkins, whose work was instrumental in Watson and Crick’s work on the molecular structure of D.N.A. Michael felt his experience peering down microscopes helped him develop the analytic eye he later brought to paintings.

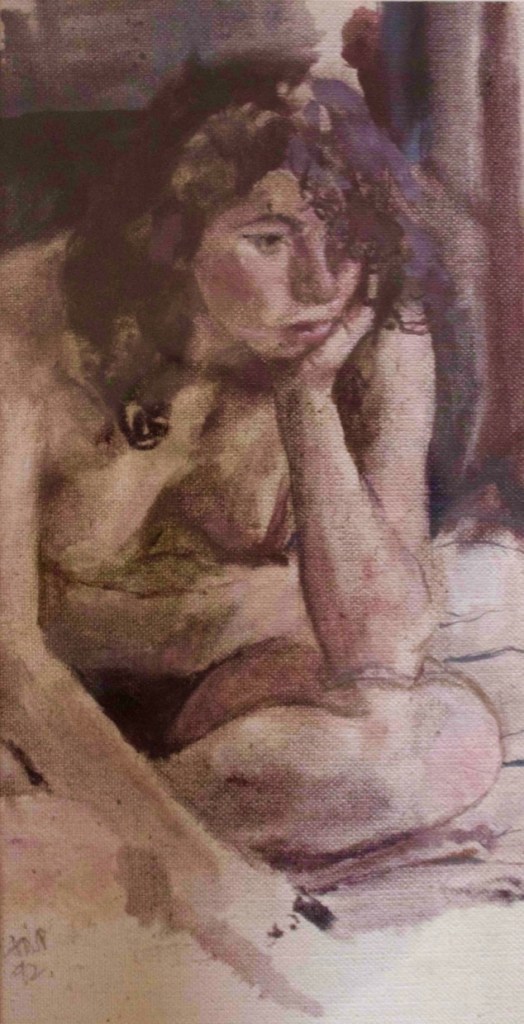

Joan in the Field, painted by Michael Ayrton, 1943.

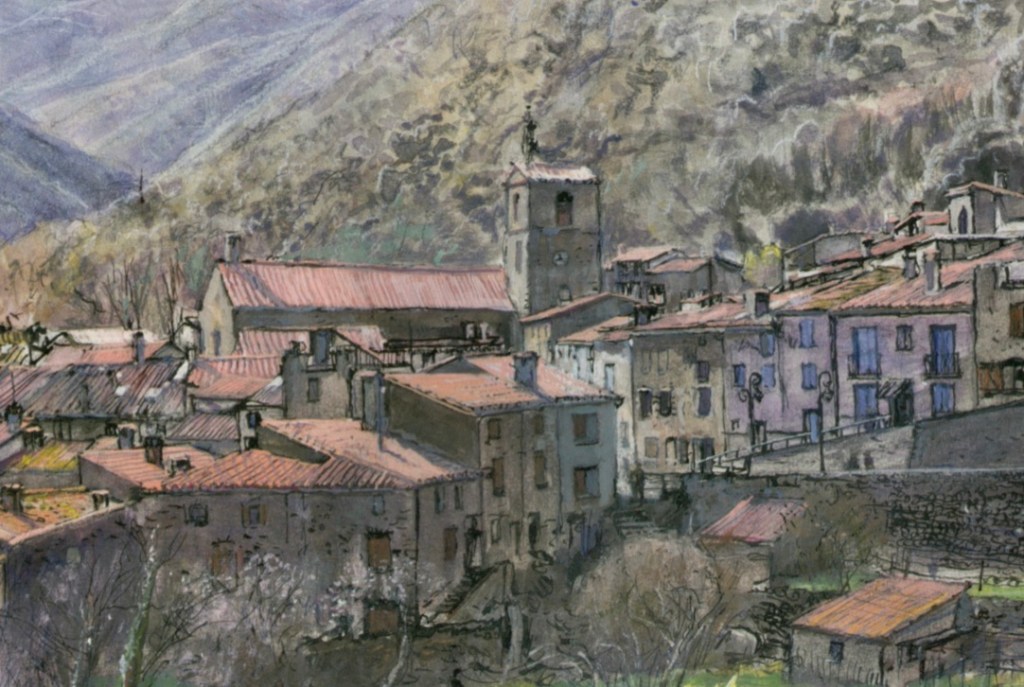

Michael also introduced me to Unity Spencer (1930 – 2017), a distinctive painter in her own right, and to Joan Foa (1919 – 1994) who had been a close associate of the artist Michael Ayrton. Dickens’ confidence in my work was very encouraging, and he also gave practical support in letting me work from his house in Rigarda in the Pyrénées-Orientales, and in arranging commissions such as the painting of ‘Joan in the Garden’ (In 1943 Joan had featured in a outdoor portrait, Joan in the Field, by Ayrton) and portraits of his friends, the actor David Bedard and others. Unlike the ‘Clement’ picture, ‘Joan in the Garden’ specifically included the human figure – not to mention the cat.

Joan in the Garden 1985 J.N.P.

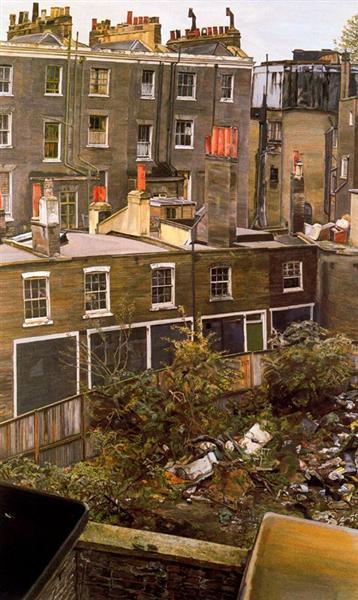

By the mid-1980s my paintings of urban gardens were becoming much more extended outdoor studies, and often include evidence of seasonal change. Begun in April 1986, it was initially the grove of dandelions growing in the lush grass of an untended lawn that attracted me to paint ‘Clement’s Garden’, but by the time I had moved on to the foreground of burgeoning chestnut leaves, the dandelion flowers had mostly become clocks. Clement’s Garden was exhibited in the 1987 R.A. Summer Exhibition, and in my first solo exhibition at the Francis Kyle Gallery. The work was exhibited yet again, thanks to the vision of the Tate curator, Martin Postle and the co-operation of Francis Kyle in arranging the loan of the painting from its owner. It was included in Tate Britain’s 2004 ‘Art of the Garden’ exhibition, in the somewhat awesome presence of works by Samuel Palmer, Lucian Freud, and Stanly Spencer.

Concurrent with the Tate garden exhibition was a small exhibition, ‘Dürer and The Virgin in the Garden’, at the National Gallery, London. Dürer’s 1503 watercolour, Das große Rasenstück, which was its centerpiece, shows a chunk of local May meadow that has been dug up, brought indoors, and placed at eye level for close-up study. The dandelion flowers have closed up, as they do when out of the sunlight, and the unpainted vellum background suggests an overcast sky. As with Freud’s ‘Two Plants’ (also painted indoors), not to mention the dandelions in ‘Clement’s Garden’, the painting implies the time and circumstances that the painter shared with the subject of his painting. Probably intended as source material for religious pictures, the common weeds depicted might well have been chosen for their symbolism. Even so, the selection is clearly intended to look like an unedited reality and probably was. Dürer’s botanical watercolours are comparable with that genre in any era, but ‘The Great Spadeful’ is rare in representing a live fragment of plant ecology.

In 1988, following the acceptance in the R. A. Summer Exhibition of a further Clement’s Garden painting, I was offered a contract by John Davies Gallery.

Clement’s Garden 1987 (J.N.P.)

In the winter months, I tried to augment my time-consuming plein-air output by working indoors or even at night. This coincided with my reading of Gombrich’s Art & Illusion (1960), particularly the chapters “Ambiguities of the Third Dimension” and “The analysis of Vision in Art” in which Gombrich quotes Leonardo da Vinci: “perspective is nothing else than seeing a place behind a pane of glass, quite transparent, on the surface of which objects behind the glass are to be drawn”. Dürer, and possibly many others, had constructed drawing devices along these lines, and I too devised a simple ‘peering aid’. My idea was to explore strange, or at least non-axial, perspectives, but another aspect was that it sped up the drawing process. The main challenge came with the painting, but again, uncertainty was restricted when working in unchanging artificial light, though I did one or two in daylight.

In the 1990s I was using three different painting locations – two friends’ gardens, Clement’s and Jacky’s, each extensive, and interesting to me both in their lie of land and state of semi-cultivation. They felt like marginal areas between nature and so-called ‘civilisation’. The human world was never absent, but my focus was on the untended, or simply unintended, aspects. The third location was an area centred on a hamlet in Lower Normandy.

IN FRANCE

A further development in my search for outdoor working space had led my wife and I to acquire a neglected property in Normandy (see above). In itself delightful, this also opened the way to new contacts and new places to paint in the margins of wildness and agriculture in the Normandy Bocage.

Old Contemporaries

In 1997, I rediscovered a fellow Hornsey alumnus, Gerry Keon. Gerry had been a leading light at Hornsey, charming, rebellious, talented, and, above all, convinced of his painterly identity. Meeting him again, I was impressed by the way he had remained true to his vocation. After many years subsidising his abstract paintings with various employments, he had found a steady job in a London parks department. Somewhat unexpectedly, he found the drawings he made in his own time becoming figurative, reflecting his fellow city-dwellers and their world.

These began to feature in large-scale paintings of urban subjects, to which Gerry often gave mythological titles. A friend suggested he should show them to a gallery, and this led to a series of impressive exhibitions at the Francis Kyle Gallery in Mayfair.

People and settings seemed to have found their way into Gerry’s paintings of their own volition. Being led in new directions through the implacable authority of the art form itself is not unfamiliar to painters; Gerry writes: “The confusions appearing on the canvas both stimulate and frustrate ideas that are emerging simultaneously and with equal confusion in my mind or imagination…. I don’t know what I’m doing, but when it happens I recognise it.“

Please click on smaller images:

Despite both of us having active, inquiring minds, Gerry being well-read and exceptionally well-informed in art History, we both approach painting with a willing suspension of any thought-processes other than a logic of technique and heightened alertness. Although our finished paintings look very dissimilar, we share a respect for the imperatives that arise from the process itself, which can be lengthy: Gerry writes: “Paintings are long and complicated enterprises. The form, which appears to exist within the materials, has to be discovered through a journey, a sequence of events neither linear nor simple. The result cannot be cajoled or forced.” (G.K. 2011)

Keon showed some of my works to Francis Kyle, who, in 1998, also became my artistic agent, continuing so until the closure of his gallery in 2014.

As well as solo shows, Kyle curated imaginative group exhibitions around literary themes, to which all his artists were invited to contribute. The first of these in which I participated was ‘The Art of Memory’ on the subject of Marcel Proust. I subsequently researched Lampedusa’s The Leopard, studied T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets and a range of other literature, as well as making related trips to Sicily, The Somme, or Little Gidding, in connection with other Francis Kyle exhibitions

I am not a ‘literary’ painter, and certainly not an illustrator, but all such studies were intrinsically rewarding. I read the entirety of Marcel Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu, (‘In Search of Lost Time’) and for the related exhibition ‘The Art of Memory’ in 2000 I contributed six canvases, all painted in places related to the book which were coincidentally not far from our Normandy property. The railway, about which Marcel fantasises in book one, and by which he travels to the fictional seaside town of Balbec in book two, is based on the single track which happens to traverse the Les Bouillons estate in a deep cutting, very near the scene of my painting ‘Herbe folle’. (For more notes on the significance of Les Bouillons click here: ACROSS THE FIELDS. )

< My first Solo exhibition at The Francis Kyle Gallery. Francis Kyle with Eleanor Pearce >

Despite Francis’ liking for literary subjects, I felt increasingly that my real subject was to do with the present passage of time, and any subtexts to my paintings, particularly the all-important implication of photosynthesis, were scientific, ecological, and topically relevant to climate change. And yet I am indebted to Frances Kyle, not only for facilitating an artistic career late in life but for introducing me to the works of Marcel Proust – literary art of an unparalleled quality….

Francis encouraged me to supply him with written notes about the paintings I offered for his gallery, arguing that published articles by critics and curators were in his experience less informed by their own insights and guesswork than by the artists’ own writings or verbal outpourings .

On the other hand, artists are themselves questioning explorers, and may be unaware of the ultimate significance of their work. Association with other artists – like Gerry Keon – is of course important, but the discerning appreciation of gallerist/dealers like John Davies, Francis Kyle or my friend the late Michael Dickens – as well as curators like Martin Postle of Tate Britain and Christine Lalumia of the Museum of the Home, can also be essential factors, both in our careers and in our artistic development.

I continued to paint in Jacky’s garden, which backs on to Alexandra Park, in North London, and also in locations in France:

Paintings in Normandy and The Pyrenees.

Old Contemporaries

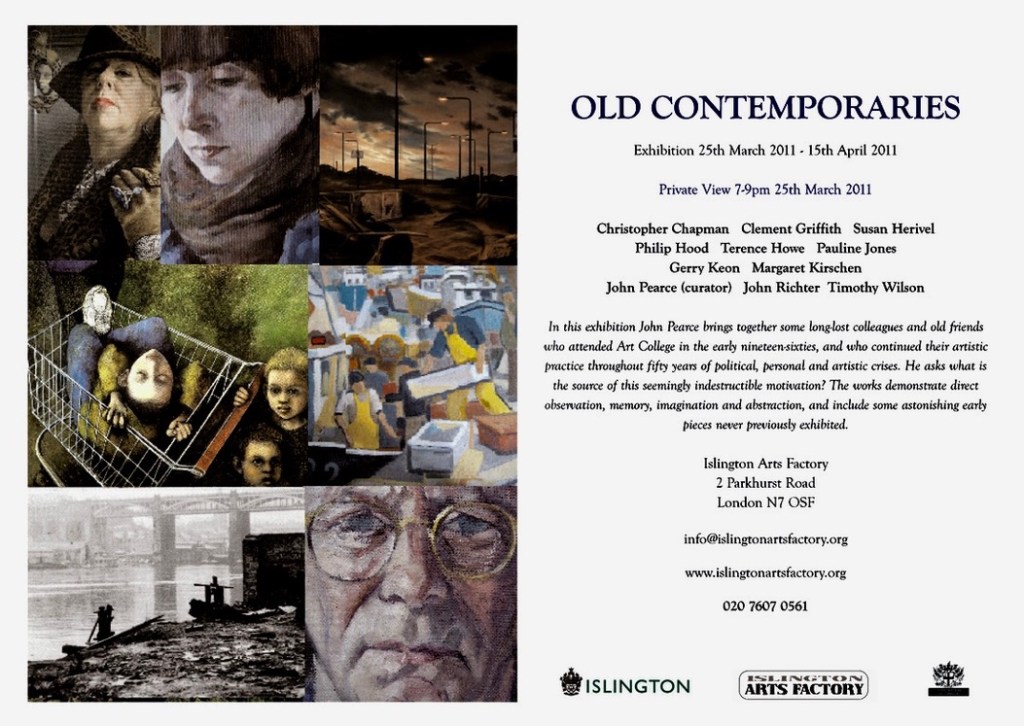

At one of Gerry Keon’s private views at Francis Kyle’s Gallery, I met up with some more of our former fellow students, and was, once again, impressed at the stubborn survival of their creativity across the decades.

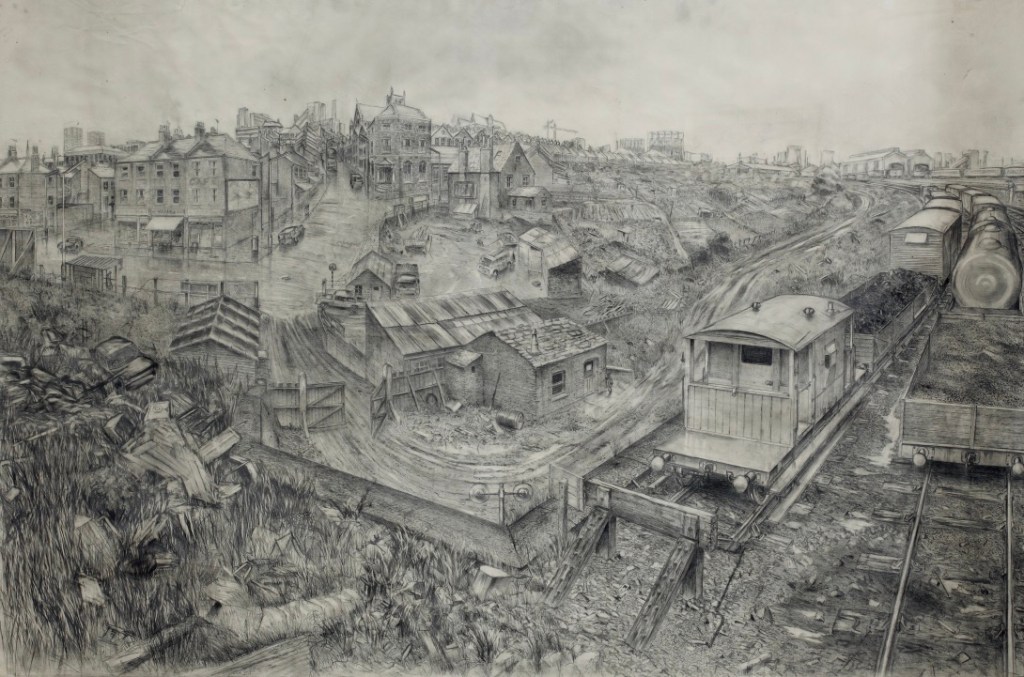

This led me to curate the ‘Old Contemporaries’ exhibition at the Islington Arts Factory in 2011. All the contributing artists had impressed me one way or another, and in some cases I was bringing to light works never before publicly exhibited, such as Clement Griffith’s remarkable 4’x6′ pencil drawing ‘Going North’, or Tim Wilson’s impressive series of self-portraits. Clement’s drawing, like Gerry’s works, had emerged, as it were, under its own impetus from imagination and memory, whereas Tim’s auto-portraits are the product of intense but dispassionate observation.

Click on these links for more about the artists in this exhibition: https://oldcontemporaries.com/2019/01/22/old-contemporaries/ https://oldcontemporaries.com/confreres-and-consoeurs/

One of my most recent paintings of Jackie’s garden was ‘The Path Half Lost’, otherwise simply called ‘The Path’. I painted it for another themed exhibition at the Francis Kyle Gallery, ‘This Twittering World’ on the subject of T. S. Eliot’s Four Quartets. Even though worked from direct observation on site, and therefore a record of a very particular experience, the painting, like Eliot’s poetry, has many resonances, ranging from my involvement with the hidden pathways of Cabala to the vivid glow of childhood recollections, set against the sombre aftermath of the Second World War.

As a child – indeed until I was ten or eleven – I had played at the edges of my father’s allotment, or on the bomb sites which nature had regenerated with such reassuring biodiversity. Though there are few parallels in poetry to T. S. Eliot’s tone of meditative soliloquy in his Four Quartets, painting surely follows a similar quest for the intersection of time and the timeless.