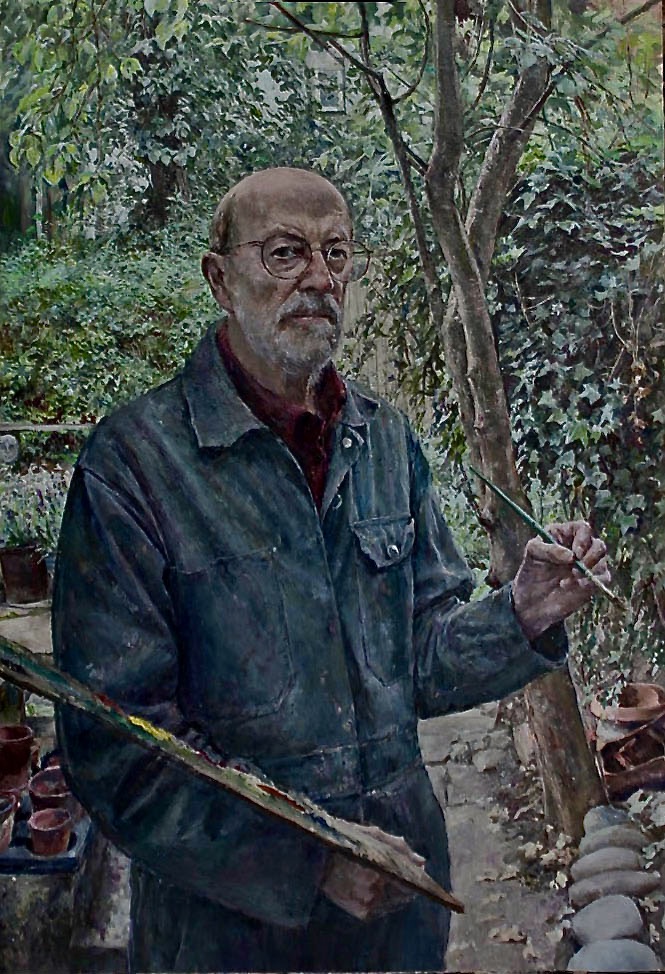

This writing accompanied the development of a painting over a period of months. It reflects the time spent on the picture and some technical and theoretical issues encountered in the performance.

Painting from Nature

“…to hold, as t’were, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of time his own form and presence.” (Shakespeare, Hamlet Act III scene 2).

Introduction:

In 2020, I had the idea to combine plein-air painting and portraiture in an outdoor portrait. Under the conditions of the Covid crisis lockdown, the only model available and keen to pose whenever and however long I require is myself.

I don’t usually include people or quick-moving creatures, because part of a garden’s charm is its different time world. But the presence of the painter is a given. Why should I not be ‘the figure in the landscape’?

In the case of a still-life, including a mirror image can add to the realism of the picture, showing that the painting has been worked from immediate observation and not from memory or imagination.

I intend to work in the open air, and I anticipate that this painting will take time. I decided to write a sort of journalistic commentary, partly to show how long it all takes, but also some of the issues involved.

If you feel the work should speak for itself you don’t have to read it – just skip the written notes and look at the pictures! But I have found that, in published pieces about my work, curators and critics have usually made as much – if not more – use of what I’ve said or written as of their own judgement and insight. (Conversely, critics sometimes object to painters straying onto their territory and waxing too publicly articulate – as in the case of R. B. Kitaj.)

Considerations arising with this self-portrait are:

1. Objectivity: Is it possible to be ‘objective’, given the fact that one does not see oneself as others do? A self-portrait can be a sort of self-assertion by the artist, or, less self-confidently, an introspective quest for self-knowledge. But any painting is as much a question-mark as it is a statement, and the self-portrait will certainly mean something quite different for the artist and viewer.

2. Significance of the reflection. The earliest self-portraits were included in major works to assert the artist’s identity – an indisputable signature. Later, in Van Eyck’s The Madonna with Canon van der Paele (1434–1436), according to Laura Cumming, the artist’s reflection is discernible in St. George’s armour, seemingly implying that the painter was also present at the scene with the Virgin & Child.

3. The use of the mirror; working from a reversed image. Early examples of self-portraiture represent the figure as if painted by someone else, in that they show the brush in the right hand. Even today, when artists usually paint themselves from their mirror image, I often find people responding to a self-portrait with ‘I never knew you were left-handed!’. It just shows how naive and uncertain people can be in the presence of art.

4. The relevance of the background setting in relation to the figure. Artists for whom, in Laura Cumming’s words, the self-portrait is ‘a chance to give their side of the story’, may well add significant subject matter in the background. A supreme example is Gustave Courbet’s, “The Artist’s Studio; A real allegory summing up seven years of my artistic and moral life, 1854-55″

5. Optical Devices: Because nowadays it is common for professional portrait painters to work with photos as well as directly with the sitter, I have diverged into some consideration of artists’ employment of optical devices, as opposed to what David Hockney calls ‘eyeballing’, which is my preferred approach.

6. References include Julian Bell’s 500 Self Portraits’ (2000) and Mirror of the World – a New History of Art (2007), Laura Cumming’s A Face to the World (2009) and James Hall’s The Self Portrait, a Cultural History (2015). I have also cited comments offered by fellow artists Gerry Keon, John Richter, Clement Griffith and Beryl-Ann Williams.

20th April 2020 I look in the mirror ‘to see myself’, but the ‘reversed’ image I see is not what others see, and evokes uncertainty rather than any other feeling relating me to it. It presumably confirms my existence, but the question remains: is a representation of my mirror image reliable? Apart from one’s availability as model, perhaps that question is partly why self-portraits are such a common recourse for artists.

Apart from that, every painting is a unique event and has to be seen in its own terms. A self-portrait might seem to be an exploration of the unknown par excellence – ‘the proper study of mankind is man’. But painting is an art of illusion, and a self-portrait finds the painter more at a disadvantage than with other subjects. Others may know us better than we do ourselves, or think they do, and an artist’s unconsciousness and preposterous ego or sense of insecurity could be painfully on show.

Julian Bell (‘500 Self Portraits’ 2000) describes self-portraiture as “a singular, in-turned art”. By contrast, Laura Cumming (A face to the World’ 2009) opines that it’s more often “an opportunity to put across one’s side of the story”.That is partly what I am doing, alongside a humbling thumbing through ‘500 Self-Portraits’ and ‘A face to the World’, but the questioning element is always there, as it is in all painting.

Art in the past has been idealised as ‘the mirror of nature’. Laura Cummings notes that, in self-portraits “…the mirror implies doubt: the direction of the artist’s gaze in the mirror means he or she confronts the onlooker with the same directness – or a similar unease.” Perhaps also reflecting the onlooker’s own unease.

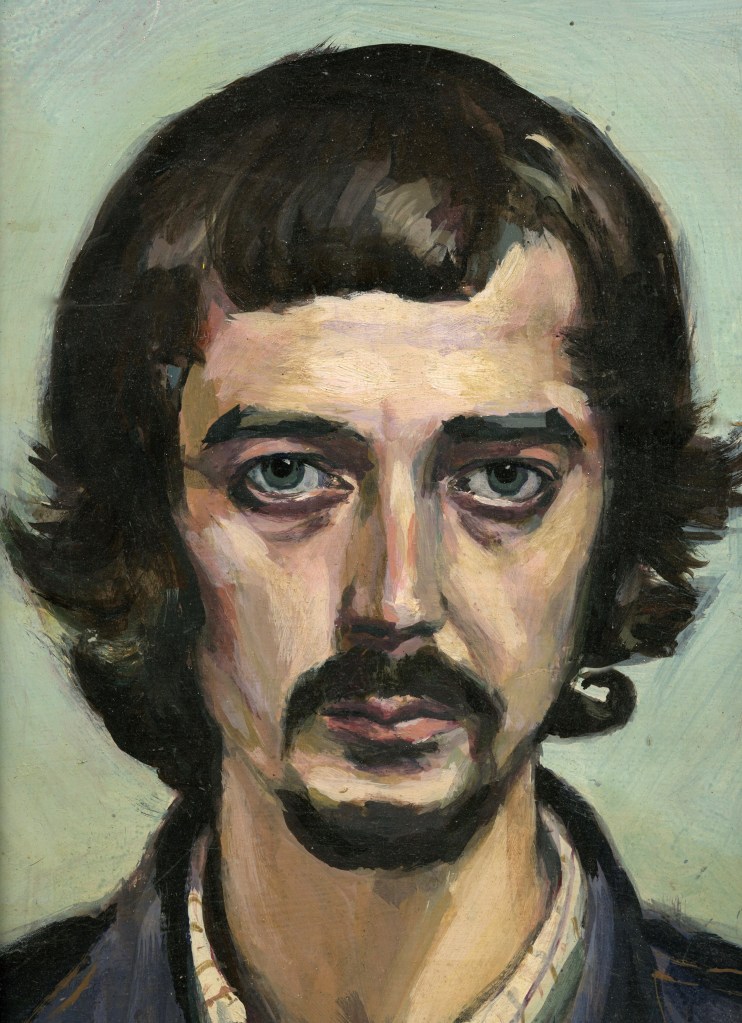

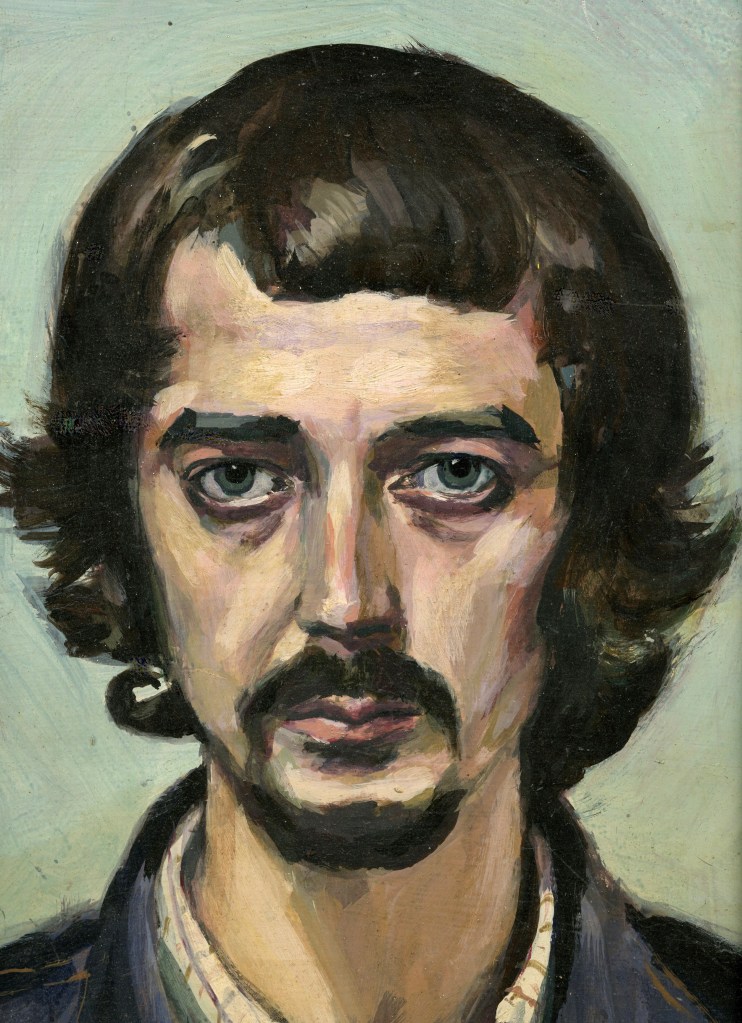

27th April 2020. I am proposing to write a little each day that I work on my own self-portrait. Work on the painting may well take a long time; no one is obliged to read it all, but it will give an idea of the time and commitment. Today I prepared the surface of a board, using sandpaper, not to make it smoother, but to roughen it and, as they say, to ‘give it tooth’.

Beginning drawing in charcoal, I felt I was really on to something!

My wandering thoughts along the way are loosely related to the dated images of the painting as it progresses. They may or may not interest the reader, but they are genuine considerations with practical implications as to how I am working.

Other painters may think very differently, or leave all such analysis to writers and critics. Though, as I remarked above, art critics or curators, quite sensibly, use material from conversations with, or writings by, the artists themselves. But artists also risk the indignation of critics for daring to explain themselves in writing as well as paint.

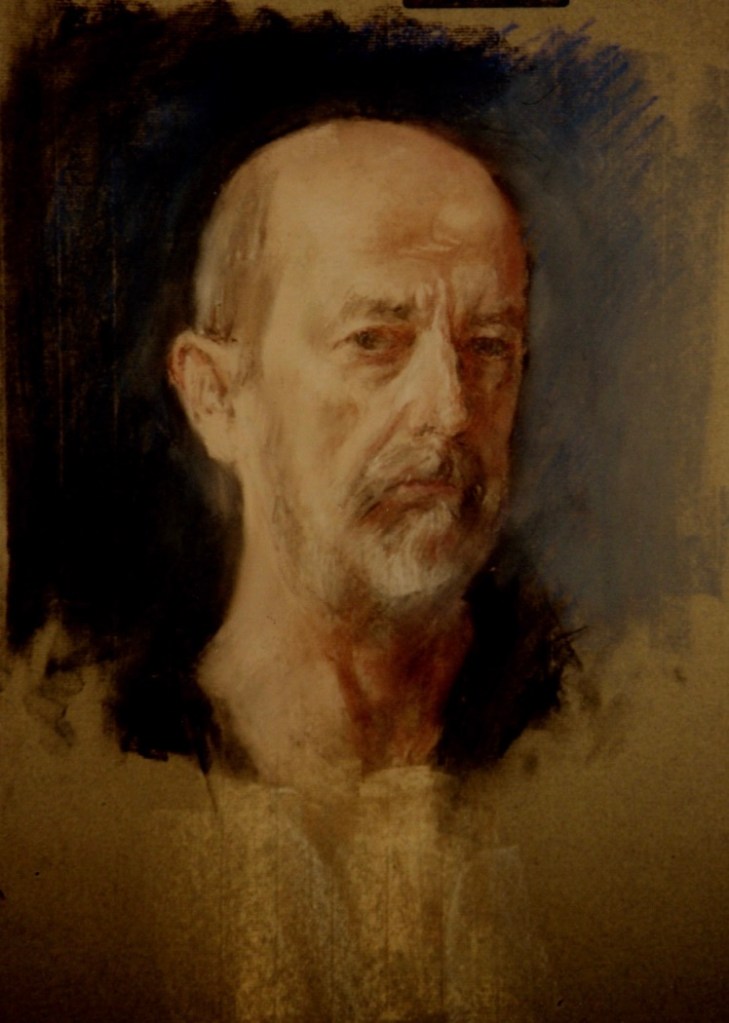

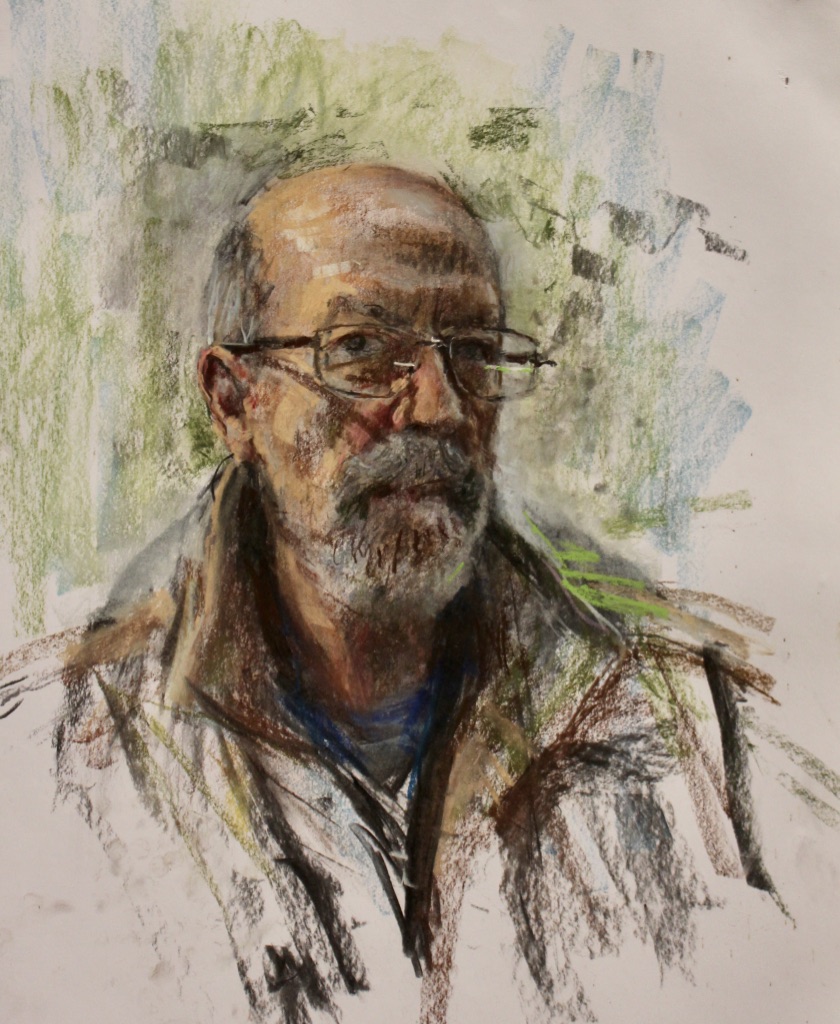

The peculiar nature of a self-portrait compounds the complexities. Just the fact that the mirror image is bilaterally symmetrical to the truth could be misleading. Horizontally ”flipped” self-portrait images can reveal another side; a different feeling quality, as with my 1970s self-portrait. But perhaps others don’t see it as I do:

30th April 2020. Albrecht Dürer’s self-portraits epitomise the contrasting, introspective, private, and public self-consciousnesses from which ‘looking glasses’ or other reflective surfaces through the ages are inseparable. Of Dürer’s 1492 pen & ink self-portrait Julian Bell writes “In his mirror lay a pathway to the soul” (Mirror of the World – a New History of Art’ 2007). By contrast, Dürer’s 1500, Christ-like self-image, is a full-face, many-faceted public statement.

Dürer’s signature A.D. logo (even said to be reflected in the fingers of his 1500 self-image) was already well-known from his wood engravings, but he is at no pains to represent himself as a mere painter or engraver – he certainly could have, had he so wished. Attempting to paint oneself painting, particularly if one is doing so from direct observation of the mirror image, can nevertheless be a technical challenge if only because the artist’s reflection cannot hold an unchanging pose. The hand that wields the brush is seldom still; least of all in critical moments of scrutiny.

Not all self-portraits show the artist in the act of painting, but I looked through Laura Cumming’s and Julian Bell’s books on self-portraiture to see how many painted themselves actually holding palettes and brushes. Most women painters seem to have done so, perhaps to make it clear this isn’t just another pretty woman painted by a male genius.

Self Portrait as the Allegory of Painting

Until the 20th C, most painters who depicted themselves in action appear either to be left-handed or to have tried to deny a mirror image, deliberately reversing it so the brush appears in their right hand and palette in the left. This is the case both with Gentileschi and Vigée Lebrun. But such painters were more than capable of invention – their public works were usually imaginative, fulfilling narrative purposes in which verisimilitude is as much an aid to suspension of disbelief as a dedication to truth. In their self-portraits, rather than defer to mirror reflections, they asserted themselves as they wished to be seen.

Self-portraits can be allegorical, have a narrative or witty subtext, and sometimes even include other people. It seems unlikely that Van der Weyden’s Self Portrait as St Luke (1435-40) was reliant on a mirror, or that Gumpp got his cat and dog to pose for his triple self-portrait (1646). He does include a mirror – doubtless an expensive status symbol at the time.

Sofonisba Anguissola both acknowledges and demonstrably surpasses her male teacher. Adélaide Labille-Guiard’s self-portrait makes a political point about women’s status in art and art education in pre-revolutionary France. Hilary Robinson (31 October 2006 Reading Art, Reading Irigary: The Politics of Art by Women) speculates that, in this picture, the artist and one of the artist’s pupils are looking at a mirror, and that Labille-Guiard is actually painting the very picture the observer sees. That is certainly what the artist wants you to think, though, If true, you have to admire her choice of overalls! In my self-portrait, the costume and background are as significant as in these works,

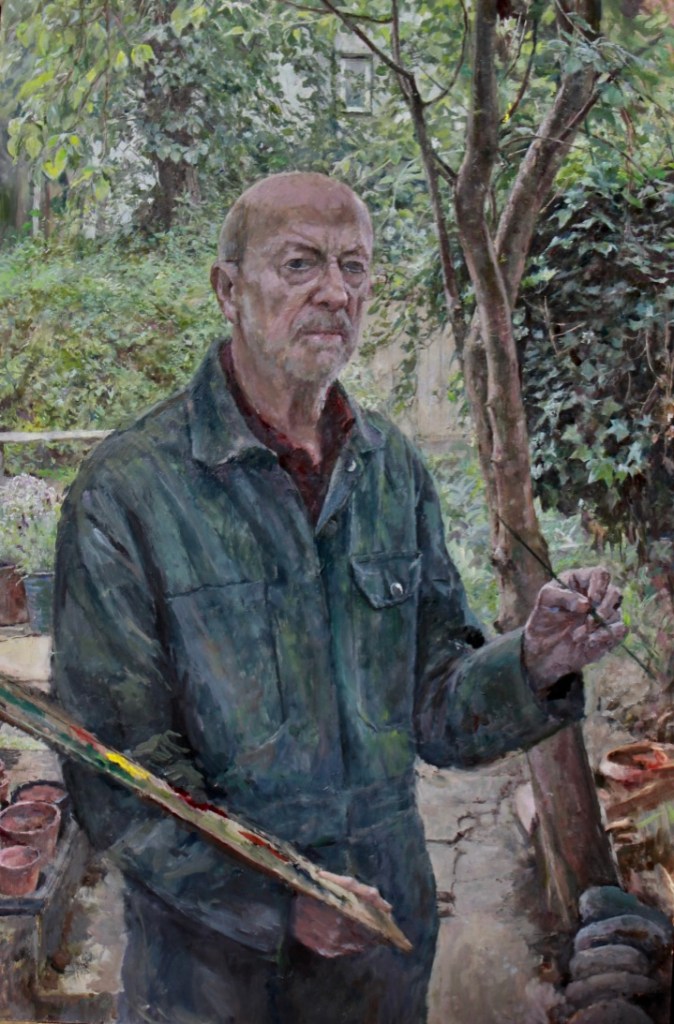

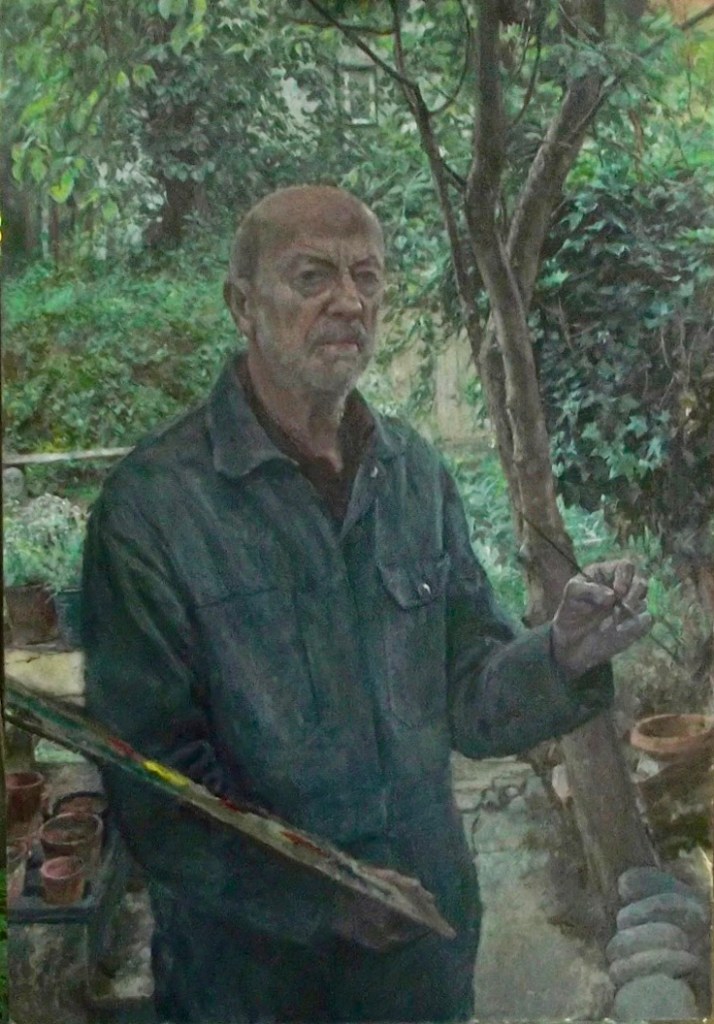

CLICK TO VIEW ENLARGED IMAGES:

5th May 2020. The issue of ‘handedness’ does seem more important when painters aim simply to portray themselves realistically as such, yet to conceal the fact they may have used a mirror. “Couldn’t you hold your brush in your left hand and paint its reflection with your right?” This solution, from my old friend Clement Griffith, hadn’t occurred to me, but perhaps it is exactly how painters in history had contrived to make themselves appear right-handed. Maybe this is what Orazio Borgianni did. If so, it wasn’t quite as ‘scrupulously accurate’, as Laura Cumming describes his self-portrait (Ibid), and the effect is indeed somewhat gauche.

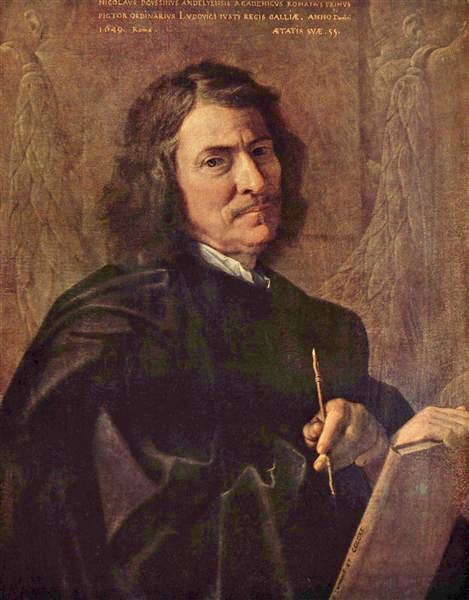

Could Poussin’s 1649 self-portrait be an early example of an artist being true to a mirror image, albeit substituting a graphic implement for a brush and a book for the canvas? In The Self Portrait, a Cultural History (2015), James Hall notes that love spells were traditionally written with the left hand, so that, despite being right-handed, Poussin depicts himself using his left hand to convey love and loyalty towards his patron. (The artist later thought better of it and painted a less intimate and charming work – without the ‘left’ hand showing – the following year.)

Jacques-Louis David was both a history painter and political activist: ‘the unrivalled image-maker of the French Revolution (Cumming 2009). When the revolutionary Marat was slaughtered by Charlotte Corday, David was one of the first on the spot, making sketches of the still-warm body for his masterpiece The Death of Marat (1793). When his friend Robespierre was guillotined, David himself was imprisoned at the Hôtel des fermes – evidently with access to a mirror.

Of Davide’s self portrait, Laura Cummings notes “a trace of bewilderment enters the moment, perhaps even tinged with grievance…” (Cummings, ‘A Face to the World, 2009) The painting may have a shocked, questioning quality, but David depicts himself primarily as a painter, with the brush in the reflected right hand.

Rembrandt’s late (1665–1669) self-portrait in Kenwood House, London seems to show the palette in his left hand, but X-rays have shown that it was originally on the left of the picture as it would have appeared in the mirror. The picture has been thought unfinished, but its power and presence are undeniable. An early example of a self-portrait that appears true to a mirror image is by Edouard Manet, and it too seems to be a work in progress -which is, after all, appropriate to the subject – and in neither painting are the hands clearly defined. None of Van Gogh’s self-portraits I know of shows his painting hand, but his 1886 self-portrait shows the palette as reflected.

7th June 2020

CLICK TO VIEW ENLARGED IMAGES:

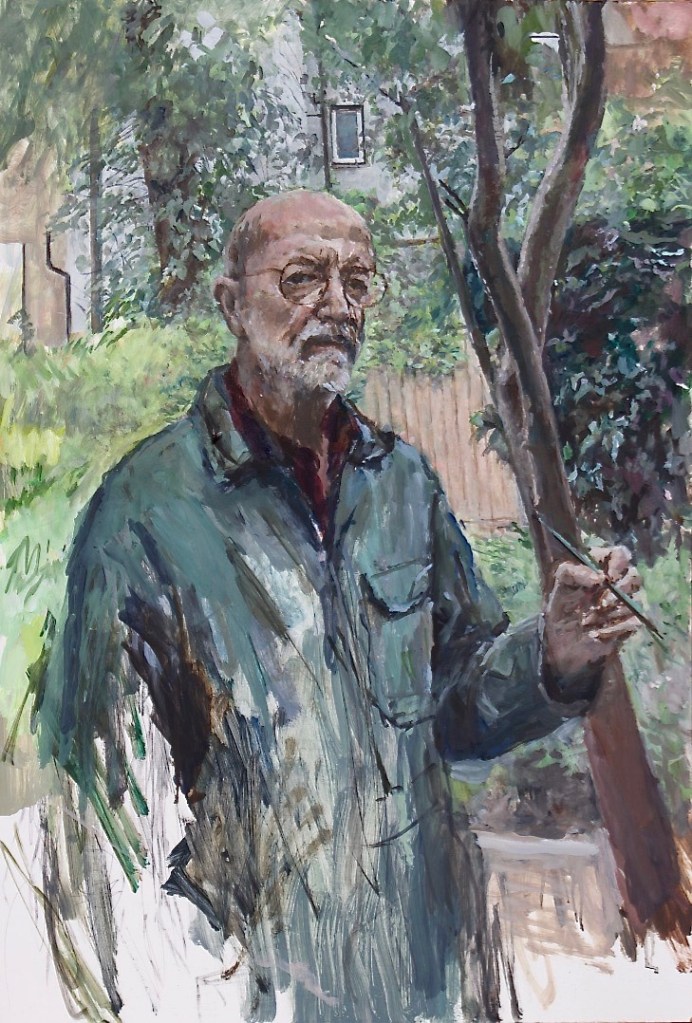

In the early stages of my painting, I repainted the small window, and the tree on the right many times, in search of a convincing relationship with the figure. It often looked wrong, but I discovered that some of this was due to unnoticed changes in the mirror’s position. I’d set it up on a sturdy easel, but brought it indoors every night, and the angular effects of even minute changes made big differences to the composition.

I employ a plumb-line and spirit level, but is my own position ever consistent? My opposite number in the mirror constantly bobs around getting in the way of things I’m trying to paint, quite apart from the problem of the ever-moving hand.

For me, the honest solution is to look intently at my right hand as it appears in the mirror, memorise, and, after making each mark, return it as nearly as possible to its former pose, thus catching the moment of attention between brushstrokes. It’s not easy.

Painting in the open air is subject to weather and seasonal changes. Usually, I find it’s best to face south (contra jour) so the light direction is relatively consistent. However, to escape observation from my neighbours – nice as they are – I have ended up in an east-west orientation. This means the light changes a lot on sunny days, so rainy, cloudy days are the best. Progress is unusually slow!

Early morning light

Working outside on a nice, cloudy day; with the mirror on a studio easel, a plumb-line (stone with a hole on a string) spirit-level, and foot markers.

29th July 2020

I emailed an image of the picture to Gerry Keon on 13th July. In his reply he wrote “…the tree has taken on a fearful presence which makes demands on your overalls to reach a similar state of heightened consciousness…” Actually, I’d spent far less time on the overalls, or the face, and had hoped getting the tree and ivy right would help me paint the figure. But maybe the problem is that the tree is naturally immobile and I in my overall am not. Perhaps I should call it ‘The Overall Effect”?

On the 29th I decided I had to reposition the brush-hand. It had looked OK when the whole painting was more loosely stated, like on 7th June. (notice also the beard trim.)

Quite tough with myself on 29th, and able to paint through the day. I couldn’t continue on the 30th, due to the light. This morning I was able to paint just a little.

Gerry’s email continued, mentioning Cézanne “…whose ocular democracy would engage with the wallpaper at the expense the model’s features…” This reminded me of one of Cézanne’s “Card Players” paintings, in which one of the figures sports a voluminous blue smock – which, like my overalls, didn’t seem quite to work in the composition.

Because, like Proust’s fictional painter Elstir, Cézanne had “an exceptionally cultivated intelligence”, but, “in the presence of reality, made himself ignorant, & forgot everything out of probity (because what one knows is not one’s own)” * he may, or may not, have foreseen that a strongly outlined, closed shape could present a compositional problem, and, as in my painting, there are issues of depicting hands and clothing.

Cézanne, in my opinion, was no less a genius than Caravaggio, but, in their very different ways, both of their stunning paintings of card players seem to me to be spatially awkward. With Caravaggio, it is part of the deception; With Cézanne it’s part of the subject.

Without the pipe-rack, Cezanne’s onlooker would seem to be standing in open sky. We know what the cheat is up to, but, despite Caravaggio’s breathtaking virtuosity, the accomplice seems neither standing nor sitting and to be looking at the back of the gull’s head.

To me, the solidity and spacial illusion is stronger in Cezanne’s picture. Despite a certain claustrophobia, the beautiful flatness of the Caravaggio painting seems at odds with its verisimilitude.

*Marcel Proust, In Search of Lost Time vol. 2, Trans. Moncrieff / Kilmartin

2nd August – Up at 6am and painting before 7. I had felt that it only needed some work on the ground but found everything was wrong. I blamed myself, but actually, the mirror had moved! After adjusting the mirror, the previous ‘mistakes’ disappeared – but other things now seem out of alignment. I continue work, unsure of what is going on.

4th August – The window cleaner says it is a ‘beautiful painting’. I say it’s awful, but has some good bits…a curate’s egg? (I definitely decided against wearing the hat!)

"It was on the fifth of August, the weather was so fair

Unto Brigg Fair I did repair,

To love I was inclined..."

5th August – Today started cloudily. I redrew parts of the figure. By 11am the day is burning bright. There was a little more ‘ground-work’, and more hopeful daubing on the overall in the warm, overcast afternoon.

(N.B. These photos have rather flattered the colour!)

9th August 2020. (This is just a preliminary draft, which I shall probably change…) It’s fairly cloudy so I’ve begun work again, with deep reluctance.

Yesterday I was perusing David Hockney’s well-researched and, to me, persuasive investigation of the significance of optical devices in art history (Hockney Secret Knowledge – rediscovering the lost techniques of the old masters,2001). Apart from my flirtation with a ‘peering aid’ in the 1980s, I have never wanted to use a photo-realist technique involving tracing an image, although I can accept that for some artists it is a valid approach. I also have to admit that the history of ‘Western’ art has been as influenced by optical devices, such as the camera obscura, as it has been by the idea of painting as the mirror of nature.

I want to paint the sleeves and other features of my overalls from direct observation – what David Hockney calls ‘eyeballing’ – an explorational drawing that ‘gropes’ for the structure. Recourse to some optical device – such as a camera – is not the object of the exercise.

It’s clear from the ‘drapery’ studies found in notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci, Dürer, Grünewald and many others, that the rendering of fabric and clothing was important to the Old Masters. In the middle ages, there were doubtless formulaic approaches to this, but Renaissance painters wanted to understand the folds, in order to be able to paint fabric convincingly, even without a model.

Not all Renaissance painters wanted to use lenses or concave mirrors. The remarkable expressive distortions, as well as fantasy, in Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, would seem to rule out a projected image, and there’s little evidence of it in Michelangelo. However, the use of light and shadow, and a ‘modernity’ in the faces, suggests that a naturalism derived from optical devices, possibly felt to be as divine as scientific, was becoming a characteristic of Western art.

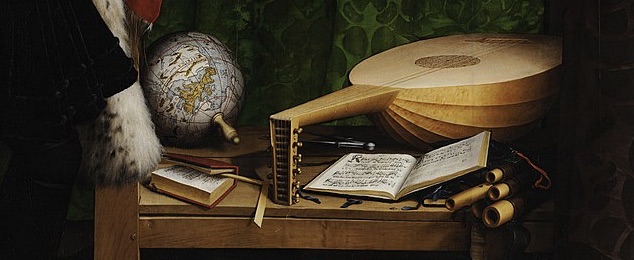

Hockney argues that the realistic depiction of fabrics, particularly the absolutely convincing way that pattern is made to follow the folds of garments in some works by Van Eyck, or the astonishingly convincing depiction of globes, astrolabes, open books of music etc. in Holbein’s ‘Ambassadors’ (1533), would be impossible without a technological extension of normal perceptive powers, just as Galileo needed to use a telescope to study the stars. As in the Renaissance, preternatural artistic gifts can coexist with scientific interests and abilities.

In the 19th C. Ingres was interested in photography. The anatomy in some of his figures can be perplexing – was his portrait of Madame Leblanc perhaps cobbled together from more than one photo? In some portraits, a sitter can almost seem upstaged by his or her fabrics and jewellery. Whether or not that’s the case with this painting by Ingres, or whether cameras are implicated, nobody seems to mind, least of all Ingres. Nevertheless, in my painting, I’d prefer not to defer to the authority of an optical device, but to follow the example of Leonardo, and study at first-hand how the fabric puckers when an arm is bent in the sleeve so that my drawing is at least a plausible hypothesis.

11th August 2020. “I know what I saw!” The naive belief in the evidence of one’s eyes has never been more questionable than now, particularly through the influence of digital imagery.

And, for that matter, how often do supposedly enlightened New Age ‘Masters’ speak of ‘higher consciousness, a ‘higher art’ or ‘360 degree awareness’, even when fake news abounds and ‘The Father of Lies’ is having a field day?

But I’m not here to settle old scores or to gripe. Today I’ve been not so much griping, or ‘groping’ as floundering!

15th August 2020. HANDEDNESS: In these 20th C self portrayals, artists depict themselves in the act of painting from direct observation in a looking glass.

CLICK TO VIEW ENLARGED IMAGES:

Max Liebermann 1925, Charley Toorop 1933, Lucian Freud 1993

Apart from Freud, who I know to have been left-handed, I assume these 20th C artists are all right-handed, and that none of them has seen fit to ‘correct’ the reflection to make it appear as if painted by someone else, or from a photograph. They all demonstrate admirable style and virtuosity in working from direct observation in a mirror.

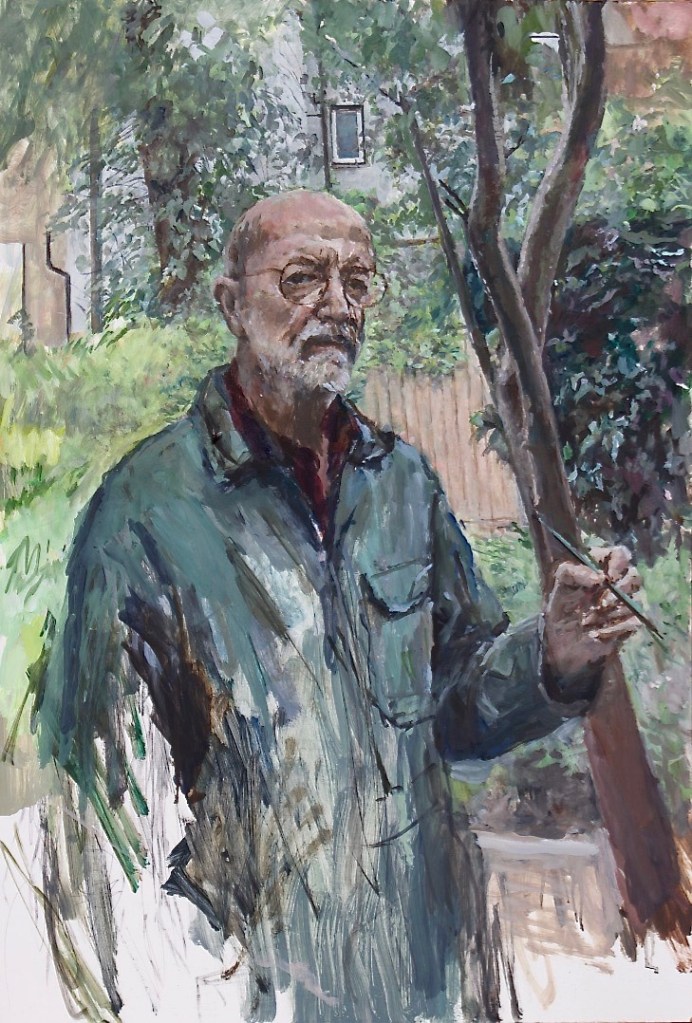

24th August 2020: There may seem to be barely perceptible changes, but the Sisyphean task of observation, erasure and repainting continues, and I feel that the composition is gradually cohering. I want the comparatively uneventful, slightly oblique surface between the pockets of the overall (the area from the sternum to the diaphragm) to feel as ‘tangible’ as, for instance, the tree & the ivy.

25th August 2020: It’s not only a question of ‘léger de main‘; I simply do not have a similar feeling for the figure and face as that which I have for the foliage.

Feeling is essential to drawing. A portrait can be dexterous and technically accurate, but without feeling, there is no likeness. Whatever I draw, I must tune in to that feeling, and it’s also the motivating force. The problem with the self-portrait is that this feeling is missing when I address the face in particular, apart from a sense that it is different and relatively accessible to me. There’s a difference in level of consciousness, to use Keon’s phrase, not just between the tree and the overall, but between the figure and the foliage.

In checking the plumb line, I discover that the mirror is very slightly tipped forward from the vertical. This matches the composition but may explain my unease about the figure, even when measurement confirms it as correct. The head seems a little too big and the palette hand too slight. I labour to set the hand to rights, but the head remains swollen.

I sent an image to another artist friend, Beryl-Ann Williams, who disagreed about the head: “I looked really hard, squinted my eyes and I can’t agree. I do identify with that feeling though that something irks you. Did you ever read The Hidden Order of Art by Anton Ehrenzweig? The painting talks to you and won’t let you rest until you obey.“ Certainly true.

28th August 2020: The artist John Richter, to whom I have sent images, writes: “…it may be the photo, but there is a suggestion that the tree is the easel, and the dark hedge on the right is the painting…” I think `I see what he means.

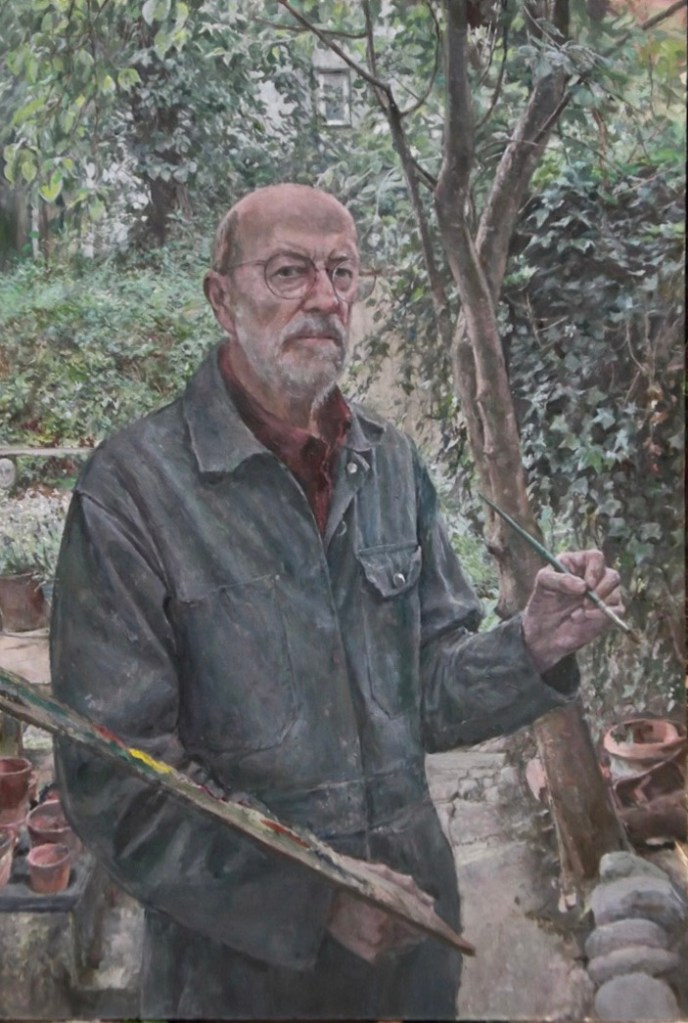

30th August 2020:

(No photo can be quite true to the painting: Left: FUJIFILM FinePix JX350; Right: Canon EOS 550D. To me, the image on the left is more integrated.)

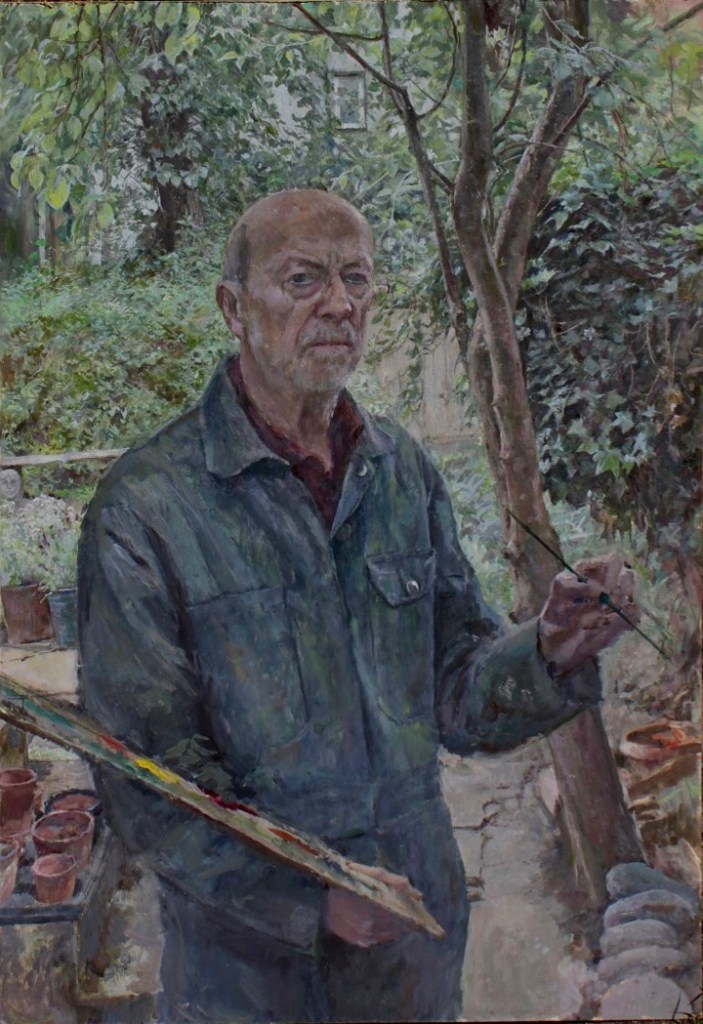

2nd September 2020: There were some very small adjustments I wanted to make. After tinkering for a while I gave up. I never end with a feeling of success or satisfaction, just of release and disengagement, when I neither want nor need to look anymore. I think this one is finished. I’ll look again in 3 weeks!! I want to let it dry so any small addition can be easily erased. I might give it a bit of a manicure. Apart from that, not much.

4th – 5th September 2020: Nevertheless I work a little on Friday, to sharpen the transition between step and the edge of the overall. Gerry Keon then writes: The base of the tree…needs stating more distinctly, that area is crucial to how the space between the hero’s leg and the ground operates and the angle of the concrete worries the eye…because that angle is in opposition to the structures on which the pots stand on the other side of our hero.

4th September 2020 – the edge between trouser and step. Oh, and now wearing glasses!

That Gerry should come up with yet another problem, now that I’ve clarified the edge of the overall, highlights that motivating sense of unease, and I misinterpret him to mean moving the base of the tree when all he said was that it needed stating more distinctly.

I’m unsure what Gerry means about the angle of the concrete. Does he mean the feeling of the ground sloping away, or the ill-defined edge next to the tree, or is it the marks on the ground? Late at night, I look again at the latest photo of the work and suddenly become aware of a structural disjunction of the foreground to the left and right of the figure.

In the morning I carefully study the ground and find the base of the tree just two inches beyond the plane of the concrete steps. The picture makes it seem too close, even though the base of the step is hidden behind the figure. The drain is also too close. It’s also hidden but is linked to marks on the concrete.

More definition is one thing – moving the base of the tree might be opening Pandora’s box, let alone a can of worms. So I have a choice – can I get away with more definition, or should I risk something which could entail a lot of restructuring? Whichever it is, I’m not doing it – at least not yet. If I leave it alone, it won’t be the first picture with anomalies.

8th September 2020: This is all I’m doing – for now at least. After some Keon-inspired alterations, there is an additional stone in the foreground. The previous five nicely rounded stones were suggestive of my head or my five fingers. The six, rather impressionist stones could signify the six days of creation – i.e. the seventh is the Day of Rest.

You may say it looks unfinished, but if it was finished the artist wouldn’t still be painting it!

10th September: But I wake up with the conviction that I’ve killed it stone dead!

11th September: John Richter writes to me: “I hope you don’t eliminate all the irregularities…….because they keep the eye on the picture surface rather than crystallising it into a frozen structure. You habitually avoid this by giving equal value to the whole image…” He has a point, and a ‘frozen’ quality is definitely a possibility, but by this time I’ve changed things.

13th Sept 2020, Gerry Keon writes: “The stones and the base of the tree seem, to me, to be completely successful and the overalls have taken on an otherworldly reality that amounts to an epiphany of some sort. I think they may find themselves becoming cult objects and their whereabouts a site of pilgrimage.”*

Such endorsements would be splendidly encouraging, especially to anyone as vainglorious as myself, but it’s too late – even were I inclined to agree. We geniuses are already out on the deep before we get our orders. (See Kierkegaard Journals, May 14th 1845)

This painting has almost spanned the equinoxes; the leaves are falling.

*In April 2021 I had a (tongue in cheek?) Facebook comment from another brilliant artist – and internationally acclaimed ‘blogger’ – Rob Adams: “Fantastic, great observation throughout, but especially in the boiler suit.”

23rd September 2020: I’ve laid my brush aside; my painting’s in a coma and it’s a question of when to switch off the life support. Maybe a last squeeze of the hand and a whispered goodbye. Artists’ hopes always die; at the last minute, Eurydice falls back into the shadows. It’s just a painting, and if there’s still a touch of medieval cubism about the perspective I don’t care.

24th September 2020: I finally focus attention on my face: do I bring it a special sensitivity or theatricality? How I want to be seen publicly is itself an expression of who I am – one that has been learned or calculated. But this painting is primarily about painting; I haven’t seen it as any more ‘about me’ than any other of my works. The slippery notion of objectivity in a self-portrait is all part of the performance.

Those furrows between the eyes – do they rhyme with the tree’s branches…? I soften them so as not to look too reproachful, though it’s how I feel about humanity’s treatment of the natural world.

Friday 25th September 2020: Many portraits and self-portraits emphasise the face and figure against a dark or understated background. Since everything in a picture carries meaning, my concept was to present myself in the kind of setting in which I usually paint – half-wild, half-cultivated nature – but in which my presence as the painter is usually unseen.

©John N. Pearce 1st October 2020

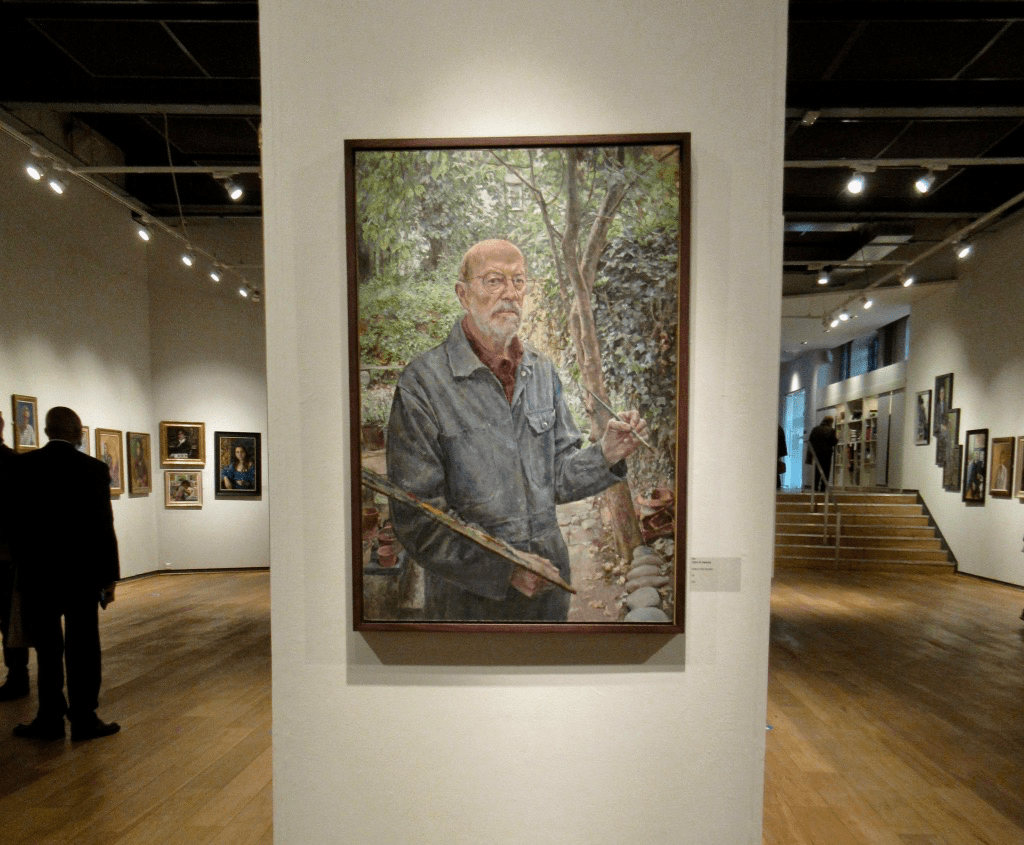

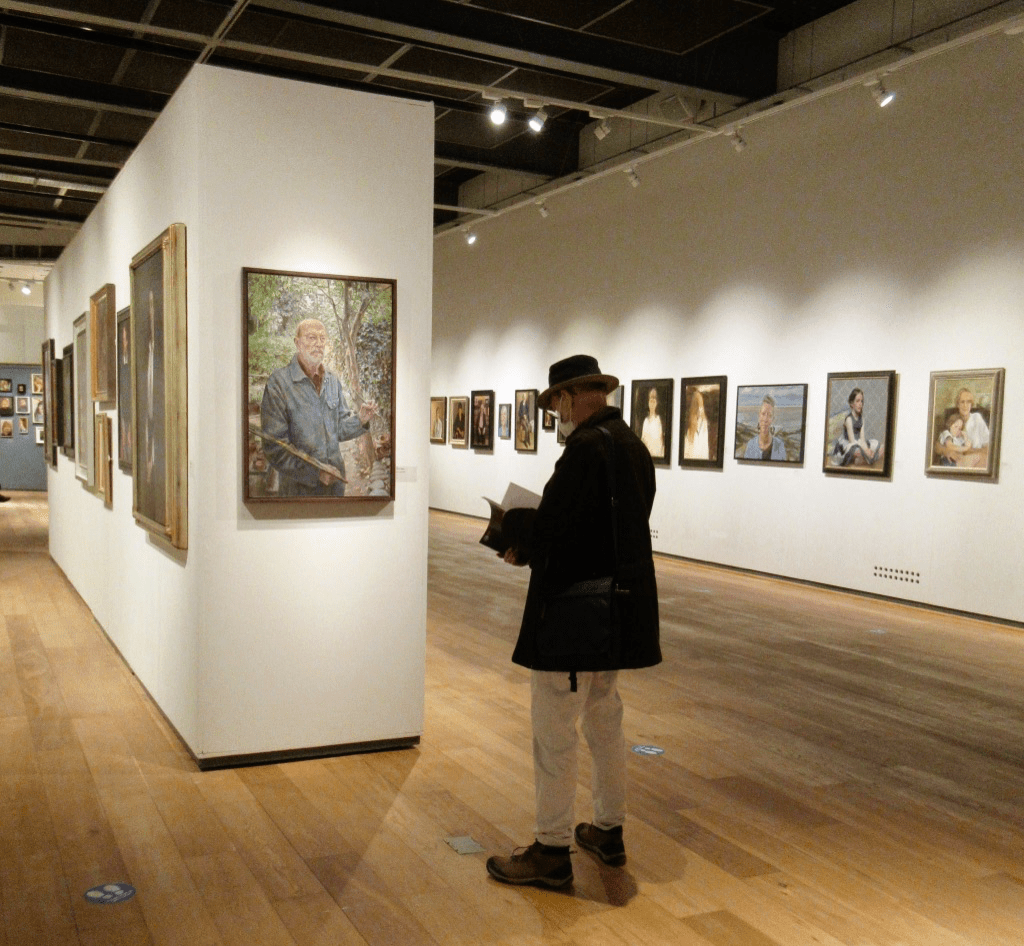

5th May 2021, At The Mall Galleries, London – Royal Society of Portrait Painters Annual Exhibition.

- HOME

- CONTINUATION 1980 – 2020

- EARLY INFLUENCES AND INTERESTS

- LATER INFLUENCES AND INTERESTS

- ACROSS THE FIELD

- EXHIBITIONS

- BOUILLONS KUB 2022

- SELF-PORTRAIT IN A GARDEN

- GALLERIES

- INDIVIDUAL PICTURES

- JOHN N. PEARCE: LIMITED EDITION PRINTS

- ABOUT – JOHN NELSON PEARCE

- CURRICULUM VITAE.

- CONTACT

- WHERE THE WAY SWINGS OFF

What a fascinating pilgrimage in self portraiture ! I really enjoyed your progress, great result.

LikeLike

Thanks for your kind remark, Marina. I expect I write too much, but the painting was quite a long as well as a revealing process. Good luck with your own artwork and research.

LikeLike